Abstract

We present a way to understand what messages may resonate with ordinary people regarding the negative effects of drugs. We identify six Questions or categories of statements, mix and match them, and present the combinations (vignettes) to ordinary respondents, over the web. The responses to the vignettes are deconstructed into the contribution of each individual element. We find clear differences by gender, age, and education, but NO patterns which lead to general knowledge. We divide the respondents by the pattern of their individual responses to the elements, which division reveals two equal size mind-sets. Mind-set 1 responds to scare tactics, facts. There is little in the way of convincing these respondents. Mind-set 2 responds to what it will to them, personally, at an emotional level. These respondents can be reached and convinced by the proper messaging.

Introduction

The notion of ‘addiction’ is not a new one. The notion of a drug problem is certainly not a recent development. Historically, the drugs involved in the world of ‘drug problems’ have been related to the products created out of poppy seeds, products that promised relief from pain, but were found to be addictive. The literature, stories, poetry, plays, is replete with depictions of people in opium dens (ref.) Famous characters in the literature of the time were featured as addicts to one or another opium-derived product, such as the legendary detective created by Arthur Conan Doyle, namely Sherlock Holmes [1, 2]. Wars have been fought over drugs, such as the Opium Wars in China.

For a long time, the topic of addiction has been one applying to alcohol, tobacco, and drugs [3] As a species, homo sapiens appears to have a predilection to become addicted to something or other. People, in fact, can be described as being addicted to gambling, addicted to a sport, a hobby, even addicted to work [4]. We hear of addiction to foods, to sweets, with the word ‘crave’ used to describe the desire for food in the same way that the drug addict ‘craves’ a ‘fix.’ People can be even be said to be addicted to each other, especially at the early stages of infatuation. This paper focuses on addiction to drugs, specifically on what one communicates to avoid addiction.

The scholarly literature is replete with studies documenting the nature of addiction. These studies usually concern the nature of addiction of people at different stages of life, in different circumstances. There is a sense that the pattern of addiction may co-vary with who the person is, and the situation in which the finds himself or herself [5–7]. There is a notion, however, that the mind of the individual may be very important in the nature of the addiction to which a person is subject [8]. The point of view about the link between personality and addiction, and the possibly ‘addiction-leaning personality’ can be found in the research reports going back three quarters of a century, to 1944 [9], and undoubtedly earlier with the works of psychoanalysts such as Freud and Jung [10].

On almost a daily basis we hear stories about the opioid crisis, a drug problem which has taken the place of previous big stories about crack and heroin, and before that morphine and opium. As a species, we humans can become addicted quite easily to many of these drugs, which cause an initial rush or feeling of wellness, but which can slowly become the master of the person, forcing that person to do anything to get the daily ‘fix, ’ (Kolodny et. al., 2015.) Addiction has become more than a problem. It has become an entire causa-belli, war cry, as activists blame food companies for making food ‘addicting’ [12].

In Western Europe drugs have been a problem in the real life, as products like heroin and morphine, so touted for health and freedom from agonizing pain have been found to be remarkably addictive. The many studies on these drugs could themselves occupy several books, just for a literature review. The social issues of addiction, the change in personality, and the creation of entire subcultures of addiction have been documented again and again. One need only go to sources such as Google® Scholar to see the dramatic, ever increasing number of papers devoted to drug dependency.

In recent years the focus on opium-based drugs has taken a back seat to the emerging problem of opiods, available by prescription (e.g., oxycontin), given for pain relief, and powerfully addictive. What started out as a new way to get rid of pain has, in turn, morphed into a social problem, involving over-prescriptions, unnecessary prescriptions to satisfy addiction, and a decline in the moral character of some individuals in the medical professional and cooperating pharmacies.

What is missing in all of these studies is a profound understanding of how to prevent drug addiction. There is now widespread appreciation of the addiction problem, especially its prevalence, and the group mantras of messages which are supposed to communicate the will to resist drugs and addictions, such as ‘Say NO to Drugs.’ These are important slogans, analogous to patriotic war slogans, memorable, rallying cries, designed to inspire. Yet there is a gaping lack of knowledge. What inspires an individual person? What specific messages can one use to communicate about avoiding drugs?

We deal here with applying the method of experimental design of messages to identify specific messages which might work. This study is not designed to provide the ultimate data, but rather designed to explore whether the methods subsumed in the science of Mind Genomics can be used to convey messages about drugs with the same efficacy as sending messages about food. The latter, messages about food and drink, are designed to persuade consumers to buy the product. The former, message about drugs and addiction, are designed to inform about the perils of addiction, with the hope of reducing drug abuse.

As part of a new effort to understand the mind of the next generation, the so-called ‘millennials, ’ we embarked on a series of projects in which millennial respondents of college age were to select a topic of interest to predefined groups of four researchers. It would be the task of this ad hoc ‘research group’ to generate the different messages to be tested within the structure of a Mind Genomics experiment. That is, we changed the typical structure of research, wherein professionals design the study, and test with the appropriate sample of respondents.

The rationale for letting the millennials become the researchers comes from the desire to understand how they respond about the topic of drugs. By instructing the millennials to come up with the test stimuli, and then test those stimuli, we discover both what is important to the millennial from the messages they choose, and how these messages convince respondents in the general population.

Method

The foundations of Mind Genomics have been treated in a variety of papers and books, to which the reader is referred [13–15] Briefly, Mind Genomics begins with a topic, asks a series of questions which ‘tell a story, ’ provides a set of answers to each question (messages), combines these messages into combinations, presents the combinations to respondents, obtains ratings, deconstructs the ratings into the contribution of the individual messages, and finally creates both new-to-the-world mind-sets, as well as a PVI, a personal viewpoint identifier, to assign new people to one of the mind-sets previously discovered through the Mind Genomics experiment.

We begin with the set of questions and answers, i.e., Questions or categories of ideas, and then the specific elements pertaining to each Question. The Questions and the elements appear in Table 1. We have phrased the Question as a question, which is how the development of the test elements occurs. The research group works with a topic, comes up with the requisite number of questions or Questions (here six), the order of the questions or Questions which thus ‘tell a story, ’ and then the relevant elements or answers to each question.

Table 1. The test stimuli.

|

|

Question A: What is the damage that drugs can wreak on your body? |

|

A1 |

Anything that makes you less than you is not for you, especially drugs and alcohol… |

|

A2 |

Keep healthy teeth…smoking and other drugs harm them |

|

A3 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill Some drugs can kill your brain cells and brain cells cannot grow back |

|

A4 |

Drug use can lower your lung capacity |

|

A5 |

Keep a healthy heart…stay away from drugs |

|

A6 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill |

|

|

Question B: How do drugs affect your personality and social life? |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when you’re down … Drugs drag you down further |

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

|

B6 |

Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

|

|

Question C: What are the effects of drugs on your family? |

|

C1 |

Family will always be there, but the “high” will go away… |

|

C2 |

Your bond with drugs can break the bonds in your family |

|

C3 |

If your children look to you as an example, you are, in effect, giving them permission to abuse drugs |

|

C4 |

Drug addicted parents can seldom offer a stable family life to their children |

|

C5 |

Every minute spent using drugs is a minute lost with a loved one |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

|

|

Question D: What financial damage does drug addiction wreak on you? |

|

D1 |

Drug use interferes with your ability, which can make it harder to earn money |

|

D2 |

The price you pay for drugs is more expensive then you think…they can cost you your life |

|

D3 |

Drugs cost a lot of money… which can be invested in more positive things |

|

D4 |

Court costs, legal fees, fines, a higher insurance rates all come with drug abuse |

|

D5 |

Drugs can make you sell your belongings for money |

|

D6 |

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings |

|

|

Question E: How are drugs associated with crime and punishment? |

|

E1 |

The #1 reason for arrest in the U.S is for Marijuana possession |

|

E2 |

Buying and taking drugs supports criminals and terrorists |

|

E3 |

Don’t be apart of crime…being under the influence can make you do things you’ll regret |

|

E4 |

Possessing drugs is a crime…a criminal record limits what you can do |

|

E5 |

Addicts guilty of NO other crime than illegal possession of narcotics, are filling the jails, prisons, and penitentiaries of the country |

|

E6 |

Almost all the opium in the U.S is made and grown in Afghanistan and funds terrorist groups |

|

|

Question F: What are other social problems emerging from the addiction to drugs? |

|

F1 |

You have NO idea how many people died getting that drug into America |

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

|

F3 |

Taking drugs definitely gives you a new lifestyle, but it is the lifestyle of a sad loser with NO prospects |

|

F4 |

Outdoor cannabis cultivation, particularly on public lands, is causing increasing environmental damage |

|

F5 |

Some of the most bitter ethnic and religious conflicts worldwide are fueled by drug income |

|

F6 |

Chronic cannabis smokers present low fertility |

When we look at the six questions in Table 1, we see that the millennials focus on the damage done by drugs. This insight, simply by itself, is valuable. It means that the younger people focus on drugs and damage, on negative effects. One might say that their questions are obvious, but not necessarily? Would, in fact, a PR company given the same task come up with the same Questions as the millennials? We don’t know. We do know, however, that this type of exercise forces the millennials to think about drug abuse in their own way, from their own perspective.

Creating vignettes by experimental design

Mind Genomics uncovers the contribution of the different elements by incorporating these elements into combinations, test vignettes. The vignettes comprise either three or four elements, a maximum of one element from a Question, but often NO element from a Question. The composition of the vignettes is dictated by an underlying experimental design, ensuring that the 36 elements are statistically independent across the set of 48 vignettes created for each respondent. Each element appears five times across the 48 vignettes, and thus is missing from 43 of the 48 vignettes. Finally, each respondent evaluates a unique set of 48 vignettes, created according to the same experimental design, but with the combinations different [13] This strategy ensures that the test vignettes cover a wide number of possible combinations. Furthermore, the strategy means that one need not know which combinations to create ahead of time. The more conventional approach would create a fixed set of 48 vignettes, present this fixed set of vignettes in different orders to respondents, average the ratings, and by so doing get a stable data set. Mind Genomics dispenses with that single set of vignettes.

The interview

The actual experiment begins with an invitation to panelists who are members of an on-line panel. These individuals have agreed to participate, in return for rewards dispensed by the company which provides the panel. Working with a panel company makes it easy to do these experiments, in return for a modest payment per respondent for the participation.

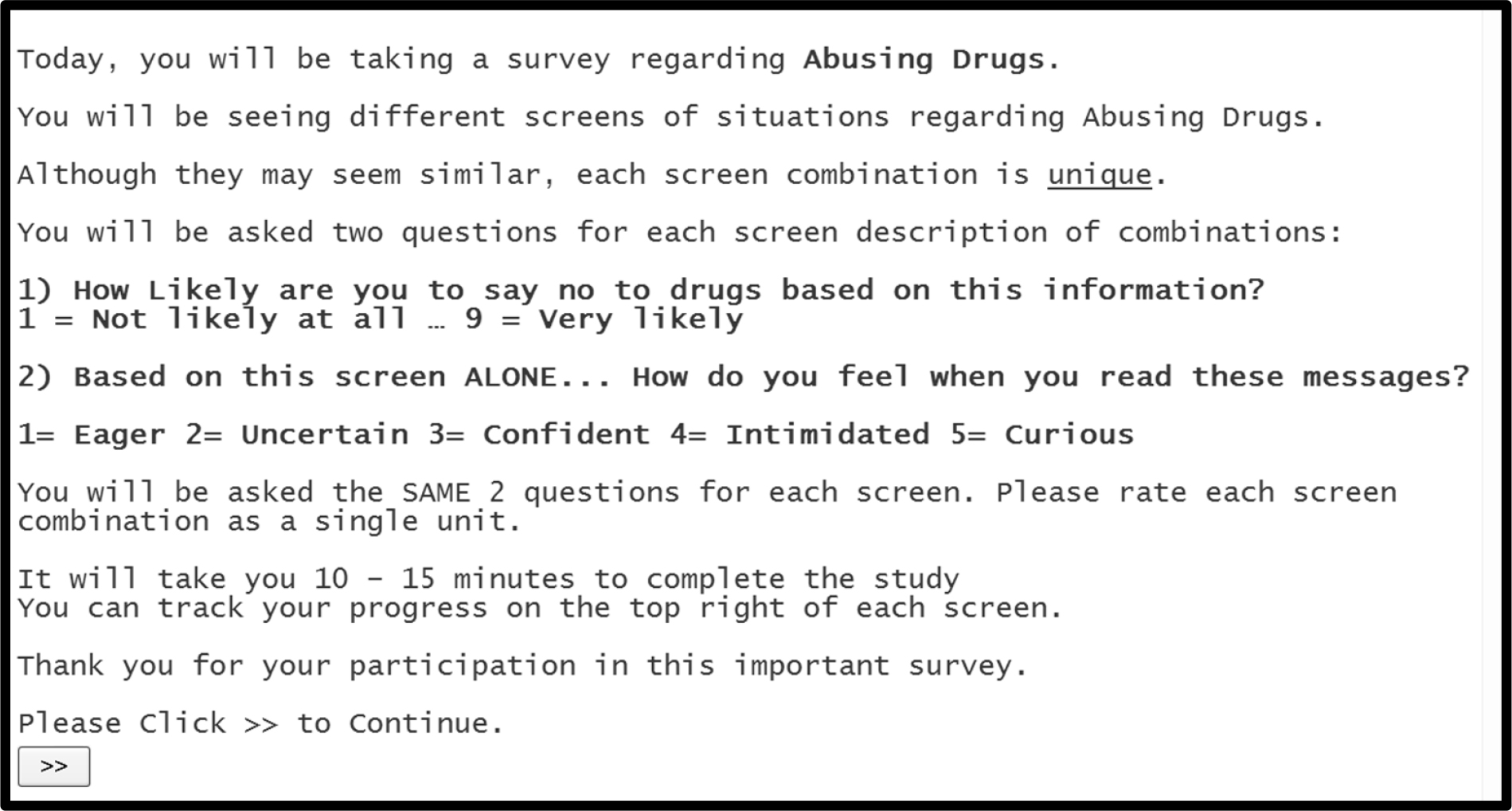

When the respondent agrees to participate, the respondent hits the embedded link in the email invitation, from which the interaction begins. Figure 1 shows the orientation page for the study. The orientation page tells the respondent a little about the study but provides NO information about what is expected. That lack of information is important. Anything in the orientation page providing greater detail is likely to set up the expectations of a ‘correct answer’ and thus bias the data in ways that are unknown.

Figure 1. The respondent introduction to the study on abusing drugs.

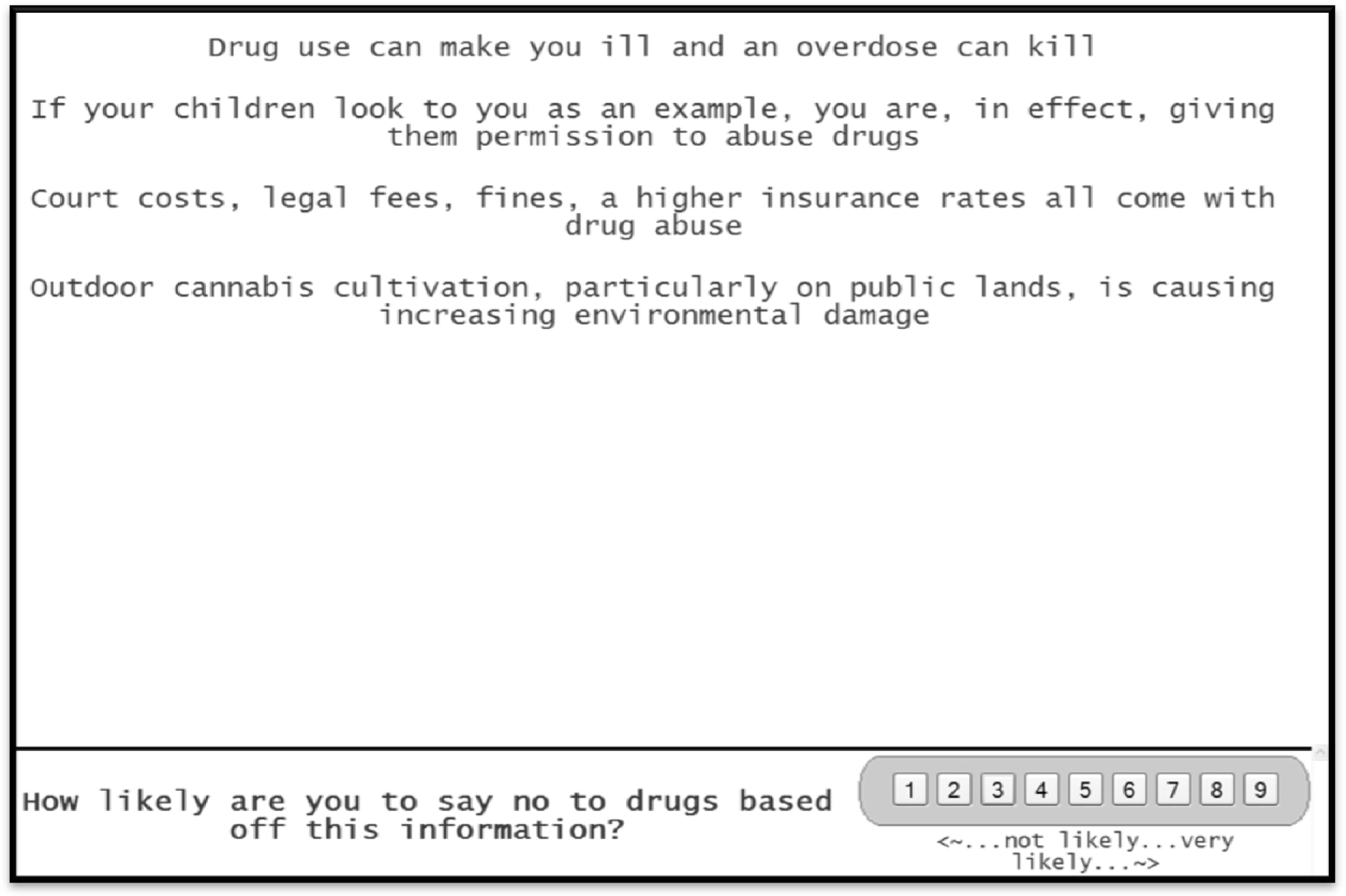

Each respondent evaluated 48 different vignettes, rating each vignette on two rating scale attributes. This paper will present results only from the first scale (How likely are you to say NO to drugs based on this information.) Figure 2 shows an example of a vignette. The experimental design dictated that 36 of the 48 vignettes would comprise four elements, one from each of four Questions, and that the remaining 12 of the 48 vignettes would comprise three elements, one from each of three Questions.

Figure 2. Example of a four-element vignette created according to the experimental design, for a specific respondent.

Transformation of the ratings from a 9-point to a binary scale and regression modeling

One of the ongoing ‘discoveries’ emerging from Mind Genomics is that users of the data report that they have difficulty understanding exactly what a scale point means. They understand the anchors of the scale (not likely and very likely, respectively), but they do not know how to interpret the values on the scale. Rather than label each point, a task which itself is fraught with biases of interpretation, we transform the rating scale into a binary scale, with ratings 1–6 transformed to the number 0, and ratings 7–9 transformed to 100. This transformation has been consistently used since 1985, and appears to work well, except for some countries wherein the respondents often ‘up-rate’ the vignettes, and which require a slightly more stringent transformation (1–7 transformed to 0, 8–9 transformed to 100.)

The transformation accomplishes its purpose, which is to make the user’s interpretation of the results simple. The numbers now deal with either NO (not interested in saying NO to drug) or yes (interested in saying NO to drugs). In order to ensure that the OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression will not crash, we add a small random number (<10–5) to each transformed number. The random number does not materially affect the results, but does ensure that the OLS regression will work for a respondent who limits his or her ratings either to the low end of the scale (1–6, all transformed to 0), or the high end of the scale *7–9, all transformed to 100).

OLS regression is the preferred way to analyze the data. OLS regression deconstructs the binary rating into the contribution of both the additive constant (basic interest in avoiding drugs, in the absence of elements, viz., an estimated baseline), and the contribution of the 36 individual elements. Even when the respondent avers that she or he simply cannot state how much of the rating is due to each element, the OLS regression reveals that contribution.

How the individual regression models fit the original 9-point ratings

During the past two decades, numerous complaints have emerged among communities of professionals engaged in polling consumers. The complaints emerge out of the reality that consumers are increasing being asked to fill out questionnaires, virtually for every action they take in the commercial environment. When a consumer purchases a product on line or in a store, when a consumer uses a bank service or a medical service, when a consumer travels and stays at a hotel, one can be fairly certain that in an increasing proportion of those transactions there will be a follow-up request for the consumer to rate the transaction and even to provide deeper responses, e.g., through an automated interview.

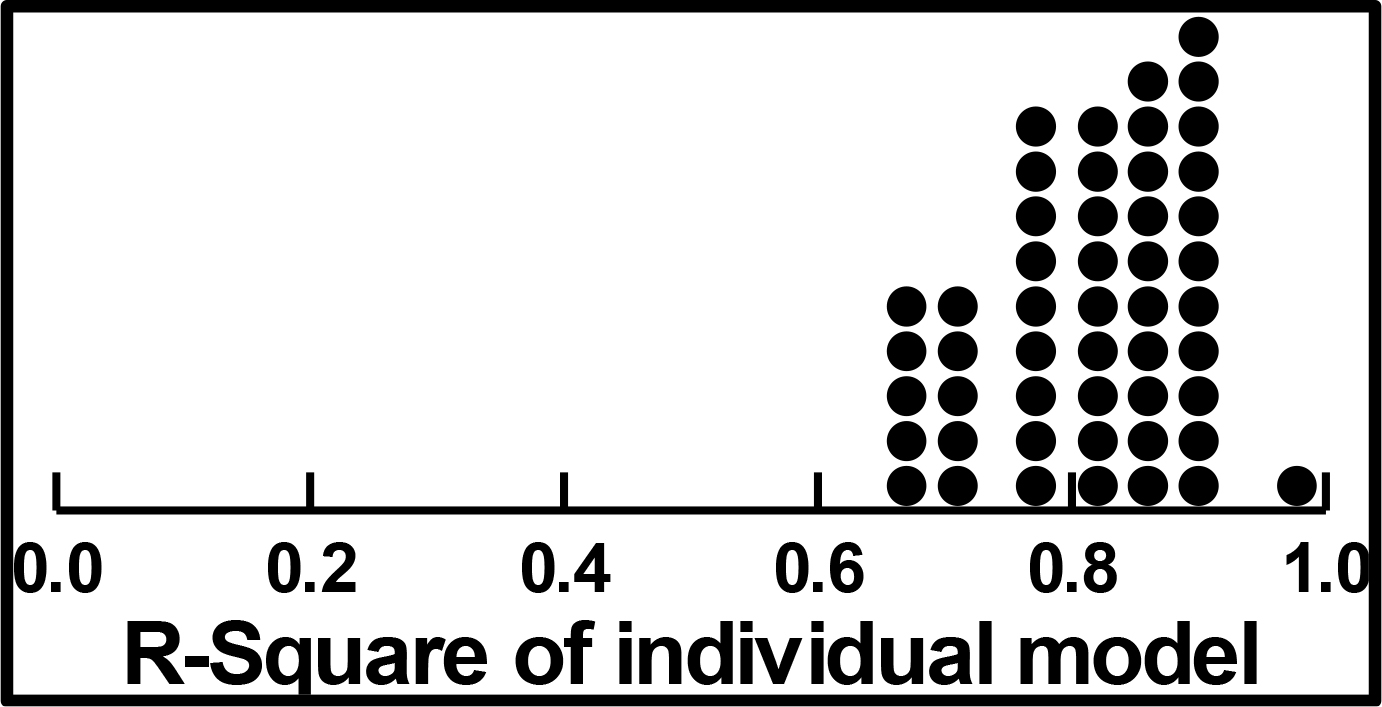

The consequence is that the respondents are increasingly hesitant to participate in the studies, and the quality of the data from those who do participate have dropped. In previous studies with Mind Genomics, we have presented the distribution of goodness of fit statistics across individuals to assess the quality of data. The statistic used, the multiple R-squared, shows the proportion of variability in the ratings accounted for by the multiple linear regression.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the R-squared values across the 50 respondents. What is remarkable is the very high individual models for goodness of fit. We attribute the quality of data to the importance of the topic. For other topics of far less social relevance, such as a credit card, the good of fit statistics are far poorer. It should be noted that whether we average good fitting models (such as those for this study) or average ‘noisy’ models (such as those for a credit card), the measure of central tendency, will still reveal what is important, and what is not important. Our focus here is simply to show how respondents pay attention to this important topic.

Figure 3. Distribution of the goodness-of-fit of the 50 individual models for Say NO to Drugs. The model relates the presence/absence of the elements to the 9-point rating (before the binary transformation).

How the individual elements drive the interest in Saying NO to Drugs

Our first substantive analysis deals with the degree to which the 36 different messages drive the response to say ‘I’ll say not to drugs.’ (see Table 2.) Recall that the dependent variable, the 9-point scale, was transformed to a binary scale, after which the OLS regression was run on the 50 individual data sets, one from each respondent, with each data set comprising 48 cases or observations.

Table 2. Performance of all of the elements as drivers of ‘saying NO to drugs’.

|

|

Say NO To Drugs (Question #1) – Coefficients of the Binary Model |

Total |

|

|

Base Size |

50 |

|

|

Additive Constant |

48 |

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

10 |

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

9 |

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when you’re down .. Drugs drag you down further |

7 |

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

7 |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

6 |

|

A6 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill |

5 |

|

C4 |

Drug addicted parents can seldom offer a stable family life to their children |

5 |

|

D6 |

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings |

5 |

|

F1 |

You have NO idea how many people died getting that drug into America |

5 |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

4 |

|

F3 |

Taking drugs definitely gives you a new lifestyle, but it is the lifestyle of a sad loser with NO prospects |

4 |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

3 |

|

E6 |

Almost all the opium in the U.S is made and grown in Afghanistan and funds terrorist groups |

3 |

|

F5 |

Some of the most bitter ethnic and religious conflicts worldwide are fueled by drug income |

3 |

|

A2 |

Keep healthy teeth…smoking and other drugs harm them |

2 |

|

C3 |

If your children look to you as an example, you are, in effect, giving them permission to abuse drugs |

2 |

|

C5 |

Every minute spent using drugs is a minute lost with a loved one |

2 |

|

D4 |

Court costs, legal fees, fines, a higher insurance rates all come with drug abuse |

2 |

|

E3 |

Don’t be a part of crime…being under the influence can make you do things you’ll regret |

2 |

|

C2 |

Your bond with drugs can break the bonds in your family |

1 |

|

F6 |

Chronic cannabis smokers present low fertility |

1 |

|

A3 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill Some drugs can kill your brain cells and brain cells cannot grow back |

0 |

|

A1 |

Anything that makes you less than you is not for you , especially drugs and alcohol… |

-1 |

|

D5 |

Drugs can make you sell your belongings for money |

-1 |

|

E2 |

Buying and taking drugs supports criminals and terrorists |

-1 |

|

A4 |

Drug use can lower your lung capacity |

-2 |

|

B6 |

Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

-2 |

|

D1 |

Drug use interferes with your ability, which can make it harder to earn money |

-2 |

|

D3 |

Drugs cost a lot of money… which can be invested in more positive things |

-2 |

|

D2 |

The price you pay for drugs is more expensive then you think…they can cost you your life |

-3 |

|

A5 |

Keep a healthy heart…stay away from drugs |

-4 |

|

C1 |

Family will always be there, but the “high” will go away… |

-4 |

|

E4 |

Possessing drugs is a crime…a criminal record limits what you can do |

-4 |

|

E5 |

Addicts guilty of NO other crime than illegal possession of narcotics are filling the jails, prisons and penitentiaries of the country |

-4 |

|

E1 |

The #1 reason for arrest in the U.S is for Marijuana possession |

-5 |

|

F4 |

Outdoor cannabis cultivation, particularly on public lands, is causing increasing environmental damage |

-5 |

Table 3. The strong performing elements, by gender, as drivers of ‘saying NO to drugs’.

|

|

|

Male |

Female |

|

|

Base Size |

12 |

38 |

|

|

Additive constant |

29 |

54 |

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

23 |

4 |

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

20 |

3 |

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

18 |

7 |

|

F5 |

Some of the most bitter ethnic and religious conflicts worldwide are fueled by drug income |

17 |

-1 |

|

A6 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill |

16 |

1 |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

16 |

3 |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

14 |

0 |

|

F3 |

Taking drugs definitely gives you a new lifestyle, but it is the lifestyle of a sad loser with NO prospects |

14 |

1 |

|

D2 |

The price you pay for drugs is more expensive then you think…they can cost you your life |

13 |

-8 |

|

E3 |

Don’t be a part of crime…being under the influence can make you do things you’ll regret |

13 |

-2 |

|

A4 |

Drug use can lower your lung capacity |

11 |

-6 |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

10 |

3 |

|

F6 |

Chronic cannabis smokers present low fertility |

9 |

-2 |

|

A1 |

Anything that makes you less than you is not for you, especially drugs and alcohol… |

8 |

-4 |

|

A2 |

Keep healthy teeth…smoking and other drugs harm them |

8 |

0 |

|

D6 |

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings |

8 |

3 |

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when you’re down.. Drugs drag you down further |

3 |

8 |

When we average the individual models from the 50 respondents, we see the following:

- Additive constant = 48 = conditional probability that the respondent will say ‘NO to drugs” in the absence of any elements in a vignette. For the total the additive constant is 48, meaning that in the absence of elements, we already have a moderate predisposition to say that they will say NO to drugs. The experimental design ensures that each vignette comprises 3–4 elements, so the additive constant is an estimated parameter. The additional motivation will come from the elements themselves.

- The sorted elements. Previous studies suggest that coefficients about 8 or higher correspond to elements which have a meaningful effect when used. We use the term ‘meaningful’ rather than statistically significant because a coefficient can have the value of 2 or 3 and be statistically significant owing to the large number of ratings, and thus the increased likelihood that even a small coefficient will be statistically significant.

- The two elements which score strongly combine both the positive and the negative. It may well be that the key to increasing donation is a combination of the so-called ‘carrot and stick, ’ and not just the ‘stick’ alone.

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal

Gender differences

We now focus only on those elements which perform strongly (coefficient > 6.51) for either males or females. Our data suggests dramatic differences, and reveals a new, unexpected pattern emerging from the additive constant and the performance of the elements.

- The study incorporated more females than males. That, however, is simply a observation, and does not affect the differences between the genders:

- The additive constant is far higher for the females than for the males (54 vs 29.) In practical terms, this means that the interesting in ‘staying NO to drugs’ is basically higher among females than it is among males. In the absence of elements, the conditional probability of a female saying “NO” is almost twice as high as the conditional probability for a male.

- Males respond very strong to some of messages, however, with coefficients of 15 or higher, a value that has been operationally accepted as a very strong driver of the dependent variable, in our case the likelihood of saying NO.

- The strong messages for male are primarily emotional and personal, bringing in the respondent, but also talking about the negatives of drugs. The only exception is the element talking about ethnic and religious conflicts, which do not bring in the respondent to the element, but simply state a fact.

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal

Drugs can limit the friends you keep

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from

Some of the most bitter ethnic and religious conflicts worldwide are fueled by drug income

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications

- There is only one strong message for females, the one which talks about friendship.

Friends are there to help when you’re down … Drugs drag you down further

Age differences

Do we see the same strong differences by age that we did by gender? Table 4 shows us that the three age groups exhibit virtually the SAME additive constant, 47–49. The quite large differences emerge in the performance of the elements.

Table 4. The strong performing elements, by age, as drivers of ‘saying NO to drugs’.

|

|

|

Age 18–29 |

Age 30–52 |

Age 53+ |

|

|

Base Size |

13 |

19 |

18 |

|

|

Additive constant |

47 |

49 |

48 |

|

|

Age 18–29 (Respond to concrete information) |

|

|

|

|

F1 |

You have NO idea how many people died getting that drug into America |

18 |

-1 |

3 |

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

13 |

6 |

10 |

|

F5 |

Some of the most bitter ethnic and religious conflicts worldwide are fueled by drug income |

12 |

-11 |

12 |

|

C2 |

Your bond with drugs can break the bonds in your family |

11 |

-7 |

4 |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

9 |

4 |

5 |

|

D3 |

Drugs cost a lot of money… which can be invested in more positive things |

9 |

-8 |

-4 |

|

D5 |

Drugs can make you sell your belongings for money |

9 |

-4 |

-5 |

|

A6 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill |

8 |

4 |

2 |

|

|

Age 30–52 (Appeal to emotion and well-being) |

|

|

|

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

-3 |

12 |

14 |

|

A2 |

Keep healthy teeth…smoking and other drugs harm them |

-9 |

10 |

1 |

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

4 |

9 |

8 |

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when you’re down … Drugs drag you down further |

-3 |

7 |

13 |

|

|

Age 53+ (information that a parent might convey to a child) |

|

|

|

|

F3 |

Taking drugs definitely gives you a new lifestyle, but it is the lifestyle of a sad loser with NO prospects |

3 |

-7 |

16 |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

-5 |

3 |

12 |

|

E3 |

Don’t be a part of crime…being under the influence can make you do things you’ll regret |

-11 |

3 |

9 |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

-4 |

2 |

9 |

|

C4 |

Drug addicted parents can seldom offer a stable family life to their children |

5 |

1 |

9 |

|

C3 |

If your children look to you as an example, you are, in effect, giving them permission to abuse drugs |

-5 |

-1 |

9 |

|

D6 |

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings |

-1 |

5 |

8 |

|

E6 |

Almost all the opium in the U.S is made and grown in Afghanistan and funds terrorist groups |

1 |

1 |

8 |

- The types of messages which drive the different ages to say NO suggest patterns, but there may be some elements which perform well but depart from that pattern. Nonetheless, Table 4 suggests different types of information to which the three age-groups respond:

- Age 18–29: They respond to concrete information, messages which paint a clear ‘word-picture.’

- Age 30–52: They respond to messages which talk about the loss of ‘feeling good.’

- Age 53+: They respond to messages which sound very much like a parent or older adult might convey to a younger person.

Where the person lives

The three groups differ in the additive constant (especially city versus rural and suburban), as well aa differing dramatically in the messages which drive each group to say ‘NO to drugs’ (Table 5.)

Table 5. The strong performing elements, by where one lives, as drivers of ‘saying NO to drugs’.

|

|

|

Rural |

Suburban area outside a city |

City |

|

|

Base Size |

14 |

20 |

16 |

|

|

Additive constant |

42 |

46 |

56 |

|

|

Rural – Elements which deal with about drugs and bad endings |

|

|

|

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when your down … Drugs drag you down further |

19 |

4 |

-1 |

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

14 |

11 |

4 |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

12 |

4 |

-2 |

|

B6 |

Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

12 |

-5 |

-12 |

|

C3 |

If your children look to you as an example, you are, in effect, giving them permission to abuse drugs |

12 |

5 |

-12 |

|

E6 |

Almost all the opium in the U.S is made and grown in Afghanistan and funds terrorist groups |

12 |

2 |

-3 |

|

D6 |

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings |

11 |

2 |

2 |

|

C5 |

Every minute spent using drugs is a minute lost with a loved one |

10 |

1 |

-2 |

|

|

Suburban – Bad for your wallet, your family, your social life |

|

|

|

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

8 |

22 |

-7 |

|

A6 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill |

5 |

15 |

-9 |

|

F1 |

You have NO idea how many people died getting that drug into America |

-4 |

12 |

6 |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

9 |

10 |

-2 |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

7 |

10 |

-9 |

|

A2 |

Keep healthy teeth…smoking and other drugs harm them |

6 |

8 |

-8 |

|

D4 |

Court costs, legal fees, fines, a higher insurance rates all come with drug abuse |

5 |

8 |

-9 |

|

|

City – Very little reaches them, other than changing lifestyle |

|

|

|

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

4 |

7 |

10 |

|

F3 |

Taking drugs definitely gives you a new lifestyle, but it is the lifestyle of a sad loser with NO prospects |

-10 |

7 |

12 |

- The additive constant, the basic proclivity to say ‘NO to drugs’ is higher for those respondents who live in the city, lower for those in a rural area.

- Rural – talk about drugs and bad endings.

- Suburban – talk about the financial problems with drugs, and the difficulties with family and social life.

- City – very little reaches them except other than it eventuates in a less pleasant social life.

The respondent’s education

We see substantial differences by education, as shown by in

Table 6. The differences do not tell as clear a story as did the differences among the previous complementary subgroups.

Table 6. The strong performing elements, by one’s education, as drivers of ‘saying NO to drugs’.

|

|

|

Completed high school |

Some |

College Vocational School |

|

|

Base Size |

10 |

17 |

23 |

|

|

Additive constant |

64 |

30 |

55 |

|

|

High School – High constant, NO specifics |

|

|

|

|

|

Some College-NO clear pattern, but many elements drive positive response of ‘Say NO’ |

|

|

|

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

-2 |

20 |

2 |

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

1 |

19 |

6 |

|

D6 |

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings |

-6 |

18 |

-1 |

|

C5 |

Every minute spent using drugs is a minute lost with a loved one |

-3 |

17 |

-7 |

|

C4 |

Drug addicted parents can seldom offer a stable family life to their children |

-2 |

14 |

1 |

|

A4 |

Drug use can lower your lung capacity |

-13 |

14 |

-8 |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

-5 |

10 |

4 |

|

A2 |

Keep healthy teeth…smoking and other drugs harm them |

-14 |

8 |

4 |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

-10 |

11 |

3 |

|

A3 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill Some drugs can kill your brain cells and brain cells cannot grow back |

-7 |

8 |

-3 |

|

F6 |

Chronic cannabis smokers present low fertility |

-3 |

11 |

-5 |

|

A1 |

Anything that makes you less than you is not for you, especially drugs and alcohol… |

-13 |

10 |

-5 |

|

D2 |

The price you pay for drugs is more expensive then you think…they can cost you your life |

-19 |

11 |

-6 |

|

D1 |

Drug use interferes with your ability, which can make it harder to earn money |

-10 |

11 |

-9 |

|

B6 |

Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

-3 |

8 |

-11 |

|

E4 |

Possessing drugs is a crime…a criminal record limits what you can do |

-7 |

8 |

-12 |

|

|

College and Vocational School – Focus on a bad life |

|

|

|

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

3 |

11 |

11 |

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when you’re down … Drugs drag you down further |

-3 |

8 |

9 |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

-9 |

12 |

8 |

|

F1 |

You have NO idea how many people died getting that drug into America |

-1 |

6 |

8 |

|

F3 |

Taking drugs definitely gives you a new lifestyle, but it is the lifestyle of a sad loser with NO prospects |

0 |

-1 |

8 |

The key patterns are the following:

- Those who finished their formal education in high school show the highest additive constant, 64. They will say NO to almost everything about drugs. The specific elements do not make much of a difference, and certainly do not drive a particularly strong response.

- Those who have had some college, but did not finish, show a low additive constant (30), but they respond strongly to some elements, shown below. The elements do not suggest a specific pattern, but they seem to be the type of advice a parent might give to a child

Drugs can limit the friends you keep

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal

Addiction does more than harm your body…it can do lasting damage to your pocketbook and future earnings

Every minute spent using drugs is a minute lost with a loved one

- Those who have finished college and vocational school respond to drugs as destroying a person’s opportunities.

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from

(At least) two mind-sets for giving to ‘Say NO to drugs’

One of the key tenets of Mind Genomics is that within any sphere of experience where people make judgments, there are differences among people which are systematic, and t, for the particular topic, may be likened to color primaries, namely red, yellow, and blue, respectively. It is not that people are different, which of course they are, but rather that there are groups of ideas which ‘travel together. A person can be characterized as more likely to respond in one pattern or another. The pattern most resembling the way a person responds is the person’s mind-set.

The above-mentioned description of the mind-sets for a sphere of experience means that there are no single mind-sets across all behavior, but rather each individual sphere of experience can be described as having its own particular experience-relevant set of primaries. Furthermore, these primaries emerge from the actual topic-specific study. That is, to discover the primaries or mind genomes for ‘Say NO to drugs’ we have to do the study, and let these genomes emerge.

The statistics to uncover these genomes or primaries is quite simple:

- For each respondent, create the model relating the presence/absence of the 36 elements to the binary response, which we did before.

- Array the models as a series of rows, considering only the coefficients, and not the additive constant. Its will be the pattern of coefficients which interests us, not the magnitudes of the individual coefficients.

- Define a distance all pairs of respondents, based upon the pattern of their 36 coefficients. The distance we choose is the quantity (1-R), where R is the Pearson correlation computed using the two sets of coefficients, one for each respondent. The Pearson correlation goes from a low of -1 (perfect inverse correlation, and thus maximal distance of 2) to no relation (distance of 1), to a perfect linear relation (distance of 0.)

- Array the respondents in two groups so that the variability between the averages of the 36 coefficients in each group is high, and the variability with the groups is low. Today’s statistical packages do these analyses quickly.

- Compute the average coefficient for each element for each of the two segments or clusters. If there is a clear story, not necessarily perfect, then stop at two clusters or segments, interpret the meaning of the clusters.

- If there is no clear story, and if there is a sense that the clusters are jamming together different types of messages, then move to three segments, and look for the story.

- The objective of the clustering is to create a minimal set of reasonably different groups, with ‘different’ defined as groups about which one can write a different story. By the tine one reaches four segments, most meaningful stories emerge.

- The results from our 50 respondents suggest two equal sized groups, although equality of size is not necessary for meaningful segmentation.

- The two segments represent two mind-sets. The two mind-sets show radically different responses to the elements, as the segmentation is set up to produce. The interesting part of the mind-sets is what they are, and how does one recognize a person as having a specific mind-set. The mind-sets are not simply distributed by gender, age, where the respondent lives, and the level of education that the respondent has attained.

- Mind-set 1 comprises individuals who respond to ‘raw facts.’ They will be hard to convince. Their additive constant is 49, but there are only two strong elements

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill

You have NO idea how many people died getting that drug into America

- Mind-set 2 comprises individuals who respond strongly to word pictures about what drugs do, and what drugs will do to them. The key is that they respond to the more elaborate messages.

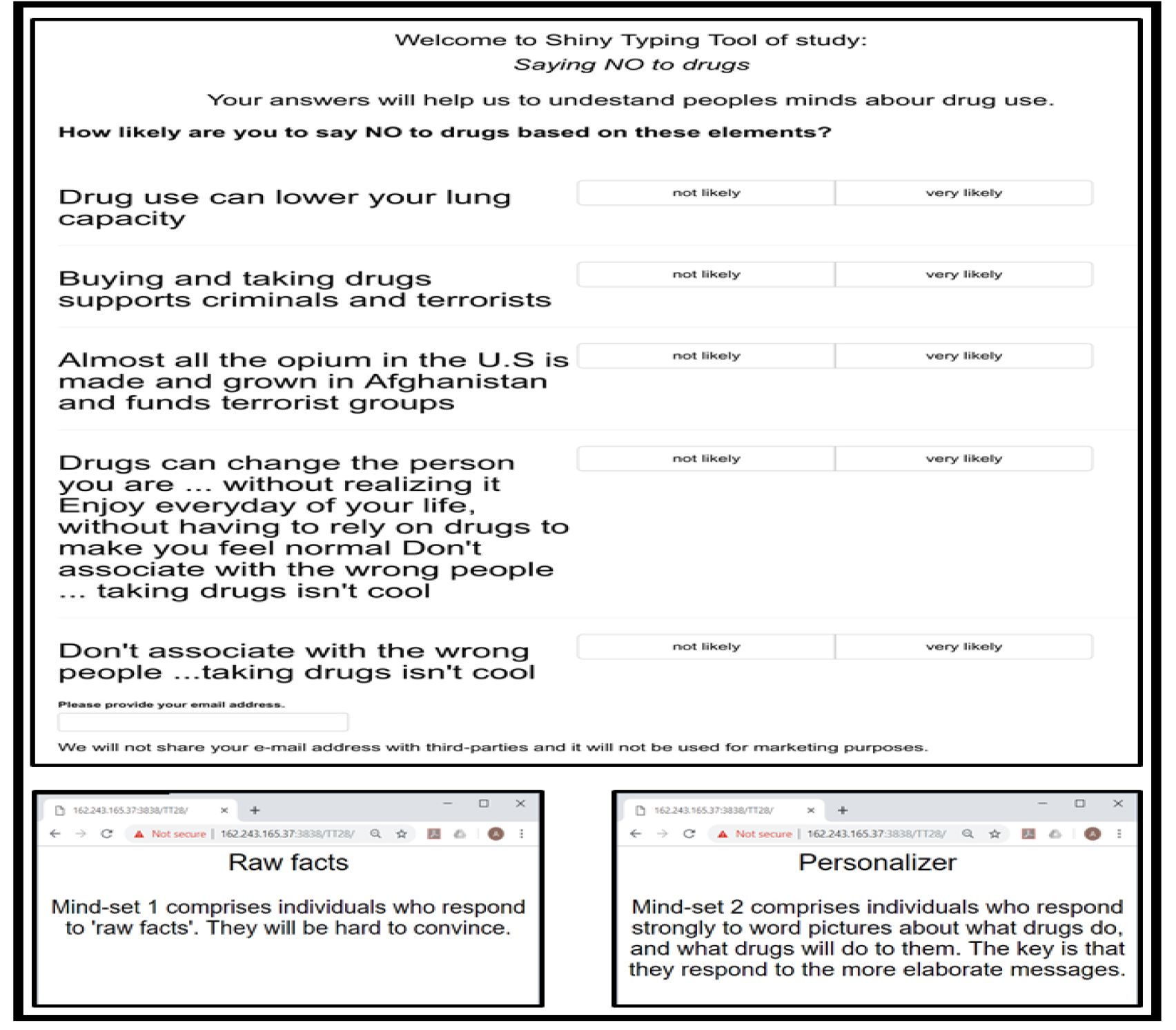

Identifying the messages and what to say

The emergence of at least two mind-sets suggests that it will be possible to adjust the message to be more effective for at least one of the two mind-sets, the Personalizer (Mind-Set 2.) These respondents react to descriptions of what drugs do, and how drugs affect their lives. These respondents react strongly to the messages that have been used to combat drug dependency. Sadly, however, they comprise only half the population, and generally are difficult to discover if all one knows is age, gender, and where one lives. Just because a person has a certain profile in terms of geo-demographics or even in terms of interests, attitudes, and behaviors does not mean that one will belong to one mind-set or the other.

What is needed is a way to penetrate the mind of a person, early on, uncover the mind-set of a person, and make sure that the person, as an individual, is targeted with the messages appropriate for the person’s mind-set. We see from this small study that only half of the respondents react to the standard messages used in public-service campaigns. The other half of the respondents simply do not react. Further work is needed to discover what messages are appropriate for the non-responsive mind-set.

One initial way to make great progress in finding the messaging to help ‘Say NO to drugs’ is to assign a person to one of the two mind-sets. If the person is in the responsive Mind-Set, one should simply give that individual the ‘message’ appropriate for the mind-set. If the person is in the other mind-set, i.e., the non-responsive group, the messages won’t work, but this respondent could be invited to participate to future studies of the type reported here, such studies to be done with members of the non-responsive mind-set until the proper, motivating messages are discovered.

How then does one find these people who belong to the non-responsive mind-set? One way creates a Personal Viewpoint Analyzer (PVI), a set of questions, the pattern of answers to which assigns a person to one of the two mind-sets. The method uses the pattern of coefficients in Table 7, selecting the messages which best differentiate between the two mind-sets. Figure 4 shows the PVI created specifically for this study, a device which can begin to separate new people into one of the two mind-sets. A working version of the PVI as of this writing (Spring, 2019) is located at this website: http://162.243.165.37:3838/TT28/.

Table 7. The strong performing elements, by two emergent mind-sets, as drivers of ‘saying NO to drugs’.

|

|

|

Mind Set 1 |

Mind Set 2 |

|

|

Base Size |

24 |

26 |

|

|

Additive Constant |

49 |

47 |

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – The raw facts |

|

|

|

A6 |

Drug use can make you ill and an overdose can kill |

9 |

0 |

|

|

Mind-Set 2 |

|

|

|

B5 |

Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal |

2 |

15 |

|

B1 |

Drugs can change the person you are…without realizing it Enjoy every day of your life, without having to rely on drugs to make you feel normal Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

-6 |

14 |

|

B3 |

Friends are there to help when you’re down … Drugs drag you down further |

0 |

13 |

|

F2 |

Everyone has hopes and dreams for the future, but for addicts those hopes and dreams only focus down to where the next score is coming from |

6 |

12 |

|

B4 |

Drugs can limit the friends you keep |

3 |

11 |

|

E6 |

Almost all the opium in the U.S is made and grown in Afghanistan and funds terrorist groups |

-4 |

10 |

|

C6 |

Babies of drug addicts are far more likely to be underweight and to suffer from birth complications |

2 |

9 |

|

B2 |

A person can undergo a complete personality change when under the influence of drugs |

-3 |

9 |

|

B6 |

Don’t associate with the wrong people…taking drugs isn’t cool |

-15 |

9 |

|

D4 |

Court costs, legal fees, fines, a higher insurance rates all come with drug abuse |

-5 |

8 |

Figure 4. The Personal Viewpoint Identifier (PVI) to assign new individuals to one of the two mind-sets. The pattern of responses to the five questions identifies a person as belonging to one of the two mind-sets.

Table 8. Number of mentions in the open-end question regarding reasons for avoiding drugs.

|

Reason for avoiding drugs |

Number |

|

Harmful to Self/Family Friends |

25 |

|

Too Expensive |

7 |

|

Illegal |

4 |

|

Past Addictions |

1 |

|

Bad Example for my Child/Children |

1 |

As in any work in progress, this PVI is simply a first approximation of what could be accomplished. The ideal approach would be to run 2–5 or more of these small-scale studies, changing the elements which don’t work, until one finds the elements which best put a group of 50–100 respondents into two or more clearly different, hopefully totally different mind-sets, strongly responsive to different messages. In our preliminary study we find only one of these groups. If circumstance dictate stopping here with the discovery of only one group, and messaging proceeds, that messaging should comprise elements which appeal to the other group (Mind-Set 1), which we label as ‘non-responsive’ and ‘only the facts.’

Open End Analysis

At the end of the session, and just before the study was over, the respondents were asked to write a short paragraph about the reasons that they find most compelling for avoiding drugs. The open-ends are not part of the study, per se, but rather enable the researcher to get additional information about drugs from individuals who have just been exposed to different sets of messages about what’s bad about drug.

The pattern of open-end responses suggests respondents say that they are most likely to avoid drugs because of the harmful effects (personal health) to themselves as well as to their families and friends. Cost is the next most frequently mentioned reasons. Other rationales for avoiding drugs include legal ramifications, past addiction, and a harmful example to children.

Discussion and conclusions

As of this writing (Spring, 2019), it is becoming increasingly clear that the so-called ‘drug problem’ is far more serious and insidious than ever before, primarily due to the increasing legality of some prescription drugs which cause addiction, e.g., opioids.

This paper presents an inexpensive, rapid, scalable way to attack the drug issue by understanding the mind of the individual, not treated like an addict, but rather treated like a consumer. That is, the objective is to understand how to communicate to ordinary people, before they become addicted, sending them messages. If we are to believe the preliminary numbers from a base of 50 respondents, then there are at two mind-sets. The first mind-set (‘The Raw Facts’) reacts to very little. More work is needed to find the deterring messages. The other mind-set reacts (‘Personalizer’) reacts strongly to messages about what the drug will do to them.

As we look at the increasing magnitude of the drug problem, could it be that the messaging is inadequate, and geared effectively to Mind-Set 2, the ‘Personalizer?’ Furthermore, could it be that we have not yet found the appropriate messages, if any, for Mind-Set 1, the ‘Raw Facts.’ Certainly, only one message or element among the 36 tested by this small sample suggests the need for more studies, studies that are remarkably inexpensive, easy to iterate, and scalable. Fortunately, the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier, allows us to identify the individuals who belong to each mind-set, and thus enable us to classify each respondent ahead of time.

It would be ironic if the tools of today’s marketing, specifically the notion of mind-types and consumer segmentation, could be extended to the understanding and amelioration of addiction. The irony, of course, is that the same science used to drive consumers to purchase and to consume, themselves often called addiction in the most severe cases, would now be turned into the very tool used to message people to avoid sources of addiction. Certainly, the affordability of the Mind Genomics science deserves more application to the social and personal tragedies of addiction.

References

- Dalby JT (1991) Sherlock Holmes’s cocaine habit. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 8: 73–74.

- Peschel RE, Peschel E (1989) What physicians have in common with Sherlock Holmes: discussion paper. J R Soc Med 82: 33–36. [crossref]

- Carver H, Elliott L, Kennedy C. and Hanley J (2017) Parent–child connectedness and communication in relation to alcohol, tobacco and drug use in adolescence: An integrative review of the literature. Drugs: education, prevention and policy 24: 119–133.

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Ladouceur R & Tremblay RE (2001) Gambling, delinquency, and drug use during adolescence: Mutual influences and common risk factors. Journal of gambling studies 17: 171–190.

- Hanneman GJ (1973) Communicating drug-abuse information among college students. Public Opinion Quarterly 37: 171–191.

- Kandel DB & Logan JA (1984) Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: I. Periods of risk for initiation, continued use, and discontinuation. American journal of public health 74: 660–666.

- Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB (1984) Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: II. Sequences of progression. Am J Public Health 74: 668–672. [crossref]

- Kido T & Swan M (2013) March. Exploring the Mind with the Aid of Personal Genome-Citizen Science Genetics to Promote Positive Well-Being. In AAAI Spring Symposium: Data Driven Wellness.

- Felix RH (1944) An appraisal of the personality types of the addict. American Journal of Psychiatry 100, 462–467.

- Crowley RM (1939) Psychoanalytic literature on drug addiction and alcoholism. Psychoanalytic Review 26: 39–54.

- Yamaguchi, K. & Kandel, D.B., 1984. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: III. Predictors of progression. American Journal of Public Health, 74, 673–681.

- Lindgren E, Gray K, Miller G, Tyler R, Wiers CE, et al (2018) Food addiction: A common neurobiological mechanism with drug abuse. Froniers of Bioscience (Landmark Ed) 23: 811–836.

- Gofman A & Moskowitz HR eds., (2012) Rule Developing Experimentation: A Systematic Approach to Understand & Engineer the Consumer Mind. Bentham Science Publishers.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & behavior 107: 606–613.

- Moskowitz HR & Gofman A, Inovation Inc, (2011) System and method for performing conjoint analysis. U.S. Patent 7,941,335.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J & Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21: 266–307.