Approximately one in three people in the UK report exposure to a significant traumatic event during the course of their life [1]. Traumatic events can include serious accidents or illness, physical or sexual assault, and neglect. This exposure rate is likely to be considerably higher for those working in trauma-prone occupations such as the military, emergency services, and in less developed countries where traumatic events are more commonplace [2]. Following exposure to a traumatic event, many individuals will experience a degree of short-term distress; however, the majority will recover in time without the need for formal psychological treatment. In a minority of cases, traumatic experiences can lead to psychological injuries which may manifest as adjustment disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or depression. In particular, the development of PTSD can have a profoundly negative impact on one’s quality of life, with symptoms potentially affecting one’s relationships with others, workplace performance, sleeping patterns and daily functioning. PTSD can also have adverse consequences for physical health, with a recent meta-analysis finding PTSD to be significantly associated with musculoskeletal pain, cardio-respiratory symptoms, and gastrointestinal health [3].

Diagnosing PTSD

To meet criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD, the individual is required to have been exposed to ‘actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence’ [4] either through direct contact, witnessing, or by indirectly learning that a very close family member/friend has been exposed to a violent or accidental trauma; or from an accumulation of direct/indirect exposure to aversive details of traumatic event(s) – usually through the course of professional duties (e.g. personnel working with child abuse cases, journalists reporting on violent criminal proceedings) [4]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) details four core symptom clusters (B-E in Table 1) that must be present in order to make a diagnosis of PTSD:

These symptoms must have been experienced for one month or more to meet diagnostic criteria [4]. Up until 2018 there were few differences between the classification of PTSD as described by the DSM and ICD classification systems. However, in 2018, the ICD-11 recognised both PTSD and Complex PTSD (CPTSD) as stress disorders [5]. CPTSD can develop in a subset of individuals who are either particularly vulnerable or where trauma exposure is often prolonged or recurrent, from which escape is difficult or not possible (e.g. experiences of torture, slavery, childhood sexual/physical abuse) [5]. For a diagnosis of CPTSD to be made, an individual must first meet the ICD-11 diagnostic requirements for PTSD and then three additional symptom clusters related to a Disturbance of in Self-Organisation (DSO).

Table 1. DSM-5 PTSD Diagnostic Criteria

|

Criterion A |

Traumatic stressor |

|

Criterion B |

Intrusive re-experiencing of the event (such as traumatic nightmares or flashbacks) |

|

Criterion C |

Avoidance of reminders of the traumatic event |

|

Criterion D |

Alterations in arousal and reactivity (such as hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, or irritability) |

|

Criterion E |

Negative alterations in mood and cognitions (such as persistent negative affect or self-perception, or amnesia for key parts of the trauma not caused by alcohol, head injury and/or drugs)3 |

Table 2. ICD-11 Complex PTSD Criteria

|

1. Meets diagnostic requirements for PTSD; |

|

2. Problems in affect regulation; |

|

3. Beliefs about oneself as diminished, defeated or worthless, accompanied by feelings of shame, guilt or failure related to the traumatic event; |

|

4. Difficulties in sustaining relationships and in feeling close to others. |

By definition, a diagnosis of PTSD denotes that an individual is experiencing significant functional impairment which can extend to their personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in the absence of such impairment does not constitute a diagnosis of PTSD, although may warrant other diagnostic labels, such as a trauma-related adjustment disorder.

Prevalence and Risk Factors for PTSD

Recent estimates have found the one-month prevalence of PTSD in the general UK population is 4.4% [1] with overall prevalence rates being similar between adult men and women. However, young women (16–24 years) have been found to be more likely to meet PTSD criteria (12.6% compared with 3.6% of men of the same age), although this effect declines with age [1]. Rates of PTSD also differ considerably between occupational groups, with prevalence rates of up to 20% of ambulance workers, up to 20% of war reporters, and between 7–30% of combat troops [6,7].

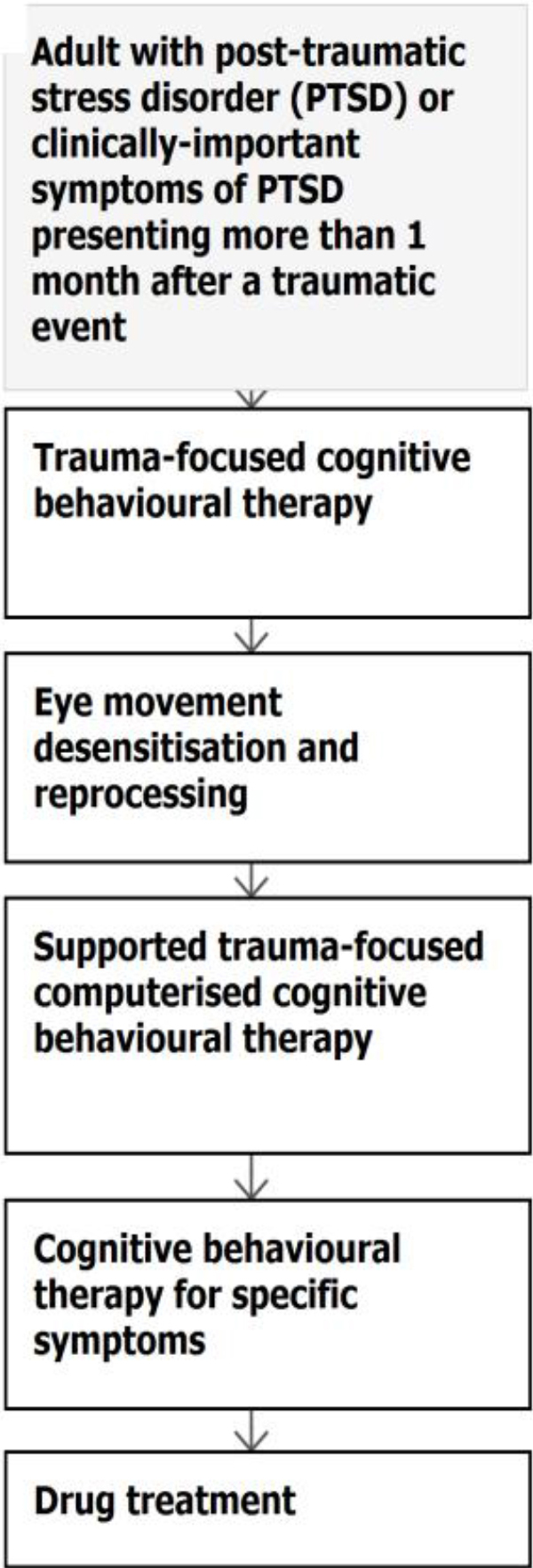

Figure 1. Flow chart for PTSD treatment. NICE 2018

While anyone can develop PTSD after a traumatic event, incidence increases with trauma severity. Other risk factors for PTSD include exposure to previous trauma, psychiatric disorder history, lower educational attainment, appraisals of the work in operational theatre as being above an individual’s trade or experience, and low unit/organisation morale or poor social support [8,9]. PTSD is also highly comorbid with other mental health disorders, with comorbidity rates often greater than 80%. The most common comorbid conditions are depression, anxiety, and substance misuse [8].

PTSD Treatment

Formal therapeutic intervention is often unnecessary in the first month following trauma exposure; in fact, evidence suggests that the early provision of psychological debriefing or trauma-counselling is potentially harmful as it may increase the likelihood of longer-term mental disorders (National Institute For Health And Care Excellence [NICE], [10]). Instead, having social support and a temporary reduction in exposure to stressors facilitates recovery in most cases. NICE guidelines advocate ‘active monitoring’ of distressed trauma-exposed individuals in the first month post-incident [10].

Evidence shows that therapies that involve an element of talking about the traumatic experiences tend to have better outcomes than supportive counselling or by managing symptoms with psychiatric medication alone [10]. Several specialist trauma-focused psychological interventions have been developed to effectively address PTSD, including exposure therapy, Trauma Focused Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (TF-CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR). TF-CBT has been found to be effective for improving PTSD symptoms following exposure to a variety of trauma types, including sexual assault, childhood abuse and combat trauma. EMDR is also a mainstream PTSD treatment although not recommended for war-related PTSD. Both treatments are generally delivered as 8 to 12 weekly sessions. NICE guidelines currently endorse TF-CBT for individuals who present with PTSD one to three months post-trauma. For individuals whose PTSD symptoms have been present for longer than three months, TF-CBT should also be offered but it is likely they will require additional sessions [10].

Medication for PTSD is not recommended as a routine first-line treatment strategy, although it can often be complimentary in treating symptoms and comorbid depression, or severe hyperarousal. NICE guidelines advise that Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI), such as sertraline, or venlafaxine is considered for adults with a diagnosis of PTSD if the patient has a preference for drug treatment [10].

Role Of Healthcare Professionals

During the course of clinical practice, healthcare professionals may encounter patients who have been exposed to a range of traumas, including providing physical care for those who have been physically injured in traumatic events. The NICE guidelines recommend healthcare professionals ask questions about trauma exposure – providing the patient with examples of potential traumatic events. Questions should also include whether the patient has experienced specific symptoms (e.g. avoidance, dissociation, nightmares, hyperarousal, etc.) [10].

While some healthcare professionals may feel ill-equipped to ask about trauma exposure or have concerns that such questions may provoke further patient distress, they should not avoid doing so. Being able to discuss a traumatic experience can be cathartic and, if distress is evident, then a referral for a formal assessment can be arranged. Asking about trauma exposure, and associated symptoms, sensitively as well as the impact that the trauma has had on a patient’s daily functioning, should be within the capability of all healthcare professionals. For example, an orthopaedic surgeon should consider and feel confident asking such questions when treating a patient who has suffered life changing injuries following a road traffic accident.

Individuals who are identified as having PTSD should be provided with appropriate guidance about the condition (e.g. the Royal College of Psychiatrist PTSD information leaflet) and advised to attend a formal mental health assessment, particularly where there are concerns about the chronicity or severity of symptoms. Information should also be provided to the family members or caregivers about supporting their loved one following a traumatic event. Families/caregivers may also help encourage individuals to attend formal assessments which is important as avoidance is a key PTSD symptom and unfortunately most people in the UK who have PTSD do not receive any professional intervention [1].

Particularly following workplace trauma, there is good evidence that peer-support programmes can be especially effective in facilitating recovery [11]. In a UK military context, investing in efforts to improve informal and formal support for trauma-exposed troops has been found to be successful, both in protecting the mental health of personnel and in reducing the stigma around mental health problems within the military [6]. Thus, it may be beneficial for healthcare professionals to be provided with information regarding local organisations and peer-support groups, such as MIND, Big White Wall or the Veterans Gateway for military veterans.

It should be noted that while the media often portrays certain groups, such as emergency service personnel or military veterans, as being particularly reluctant to seek help for mental health difficulties, a failure to seek formal support for trauma-related psychological problems reflects a societal issue rather than the mindset of specific professions [1]. Therefore, it is recommended that healthcare professionals encourage patients and colleagues with chronic and impairing trauma-related symptoms to access social support or formal treatment. A further consideration is that treatment options for more complex presentations of PTSD, while available on the NHS can be challenging to access depending on where someone lives.

As with any mental health problem, the family members of an individual suffering with PTSD can also be vicariously affected. Research has shown that spouses and children of individuals with PTSD can experience significant mental health difficulties themselves, including secondary PTSD symptoms and emotional dysregulation problems [12, 14]. The provision of psychoeducation to families, an assessment of family member’s needs, as well as emotional support may be beneficial to augment familial coping.

Summary

In summary, while most people who experience traumatic events may have short-term distress, only a minority will develop PTSD. PTSD can have a debilitating effect on not only their lives, but the lives of their families, colleagues and friends. In the initial period after a traumatic event, the majority of people benefit from access to social support and a temporary reduction in stress. For the minority who do develop PTSD, there are evidence-based talking trauma-therapies which can improve functioning and psychological wellbeing. While it is ideal to access such treatments within months of a trauma, so that the negative impact on one’s life is kept to a minimum, treatment can be effective even after a delay – allowing those with PTSD to continue to lead fulfilling lives once again, even if the full resolution of symptoms is not possible in some cases.

References

- Fear NT, Bridges S, Hatch S, Hawkins V, Wessely S (2016) Posttraumatic stress disorder. In: McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R BT (eds), editor. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Leeds: NHS Digital, Leeds, England Pg No: 991.

- Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen H-U (2016) Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: prevalence,risk factors and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101: 46–59.

- Pacella ML, Hruska B, Delahanty DL (2013) The physical health consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms: A meta-analytic review. J Anxiety Disord 27: 33–46.

- American Psychiatric A. (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) [Internet]. American Psychiatric Pub Pg No: 991.

- World Health Organisation. (2018) ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics.

- Greenberg N, Jones E, Jones N, Fear NT, Wessely S (2010) The injured mind in the UK Armed Forces. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 366: 1562.

- McFarlane AC, Williamson P, Barton CA (2009) The impact of traumatic stressors in civilian occupational settings. J Public Health Policy 30: 311–27.

- Bisson J, Ehlers A, Matthews R, Pilling S, Richards D, et al. (2007) Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry 198: 97–104.

- Iversen AC, Greenberg N (2009) Mental health of regular and reserve military veterans. Adv Psychiatr Treat 15: 2.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence N. Post-traumatic stress disorder: management (2018).

- Brooks S, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N (2018) Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: overview of the literature. J R Army Med Corps Pg No: 1–5.

- Leen-Feldner EW, Feldner MT, Knapp A, Bunaciu L, Blumenthal H (2013) Offspring psychological and biological correlates of parental posttraumatic stress: Review of the literature and research agenda. Clin Psychol Rev 33: 1106–33.

- Diehle J, Brooks SK, Greenberg N (2016) Veterans are not the only ones suffering from posttraumatic stress symptoms: what do we know about dependents’ secondary traumatic stress? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol Pg No: 1–10.

- Williamson V, Stevelink SAM, Da Silva E, Fear NT (2018) A systematic review of wellbeing in children: a comparison of military and civilian families. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health Pg No: 12: 46.