Abstract

Objective

Sweden has received a large number of asylum-seeking individuals in recent years and many refugees are in need of urgent dental care. Refugees do not usually receive regular information about the Swedish dental-care system and its regulations upon arrival. The study was aimed to examine information and experiences associated with emergency dental care among newly arrived Syrian asylum-seeking patients in comparison with Swedish patients and to monitor how the dental staff perceived these two groups of patients. The hypothesis was that the Syrian patients lacked information about the Swedish dental-care system and that they were more dissatisfied with their emergency treatments.

Material and Methods

Two questionnaires for patients and therapists relating to information and experiences in connection with emergency dental visits were produced. The questionnaires were distributed consecutively and responded to by 96% of all involved patients and care- givers.

Results

Most Syrian patients reported receiving information before treatment and, in more than 60%, from friends and acquaintances. Over 90% of all patients had a good understanding of the information and the therapy discussion during treatment. The Syrian patients received less help with their reasons for treatment, were less satisfied with the treatment and experienced more fear. The therapists had greater difficulties in interpreting the Syrian patients’ fear, their satisfaction with treatment and whether or not their expectations were met.

Conclusion

In order to achieve a mutuality in the communication and understanding between the newly arrived refugee as a patient and the dental staff, it is important to provide accurate information about the Swedish dental care system to the refugee before the first dental care visit.

There is also a need for improved skills among the dental-care providers in communicating and interpreting patients from other countries and different cultures.

Keywords

Dental staff, emergency dental visit, experiences, information, newly arrived Syrian refugees

Introduction

Internationally, as a result of wars, conflicts and oppressions, there are currently large flows of refugees, where more than 65 million people are estimated to be on the run [1,2]. Sweden is one of the largest recipient countries in Europe for refugees from developing countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Somalia and, in 2015, more than 160,000 people applied for asylum in Sweden [3].

It has been found that refugees often are affected by health problems on arrival in new countries [ 4–6]. This includes oral-health problems such as caries, periodontitis, pathological changes in the mucous membrane and damage caused by violence and torture, as well as bad habits in relation to diet, oral hygiene and smoking [6,7]. The often long and exhausting travels with limited dental care facilities, that many asylum seekers undergo, can contribute to transform simple tooth problems to significantly greater [8]. Newly arrived refugees are therefore often in need of both dental and medical treatment soon after arrival, which is often a reason for them to seek emergency care [9,10].

Asylum seekers who have applied for a residence permit in Sweden are entitled to emergency dental care, but they are not eligible for the Swedish state dental-care support [11]. The emergency dental care is governed by a regulatory framework, which often limits the treatment options for asylum seekers. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s guidelines for acute or immediate dental care for these patients often involves treatment that addresses the acute problem but does not always include the complete treatment therapy [8,12]. Information about treatment regulations, when given in conjunction with emergency treatment, could be a setback for refugees, when their expectations do not match the treatment that can be offered by Swedish dentistry [13]. Further, different cultures’ views of oral health, what constitutes good treatment and what is socially acceptable, together with previous experiences and different ways of communicating often creates insecurity, worry, anxiety and frustration for newly arrived refugees and this may ultimately contribute to misunderstandings, disagreements and conflicts [7].

The origin of this study was that the staff at a local public dental care clinic in a medium-sized city in the County of Västra Götaland, Sweden reported a working environment problem associated with the increasing number of acute treatment occasions in which newly arrived asylum-seeking refugees were the patients. The dental clinic is situated near one of Sweden’s largest refugee camps in the neighboring area. The problems experienced by the staff were that there were more disagreements and conflicts in connection with the emergency treatment of newly arrived refugees compared to Swedish patients. They usually occurred during information and therapy discussions but also during the treatment itself. According to the dental staff, the newly arrived refugees had a poor knowledge of the Swedish dental-care system, probably due to the absence of dental- care information in the introductory information from the Migration Board, which in turn created uncertainty and frustration among these patients when it came to emergency dental therapy and treatment.

In order to examine what happens during treatment, a decision was made to study the largest group of adult refugees with a more common background than from just one country. The aim was to obtain a better understanding and easier interpretation of the language and a better comparison of the refegees experiences with the experiences of the Swedish patients and the treatment staff. Syrians constituted the largest group of asylum- seeking refugees both at the public dental clinic and at the nearby refugee camp, where about 50–60% of its residents were Syrians. More than 50,000 Syrian refugees sought asylum in Sweden in 2015 [5]. Before the democracy conflict and war began in Syria in 2011, the country had a relatively well- functioning educational system, as well as health- and dental-care systems [14,15]. This implies that adult Syrians have a relatively high literacy level and also often have previous experience of both medical and dental care in Syria.

The aim of this study was to examine the frequency of information obtained about Swedish dental care before an emergency dental treatment session among newly arrived Syrian asylum-seeking patients and Swedish patients. Further, to examine the frequency and understanding of information and therapy discussions and to examine experiences of treatments during emergency visits among newly arrived Syrian asylum- seeking patients, Swedish patients and the treating staff. The hypothesis was that the Syrian patients received information to a lesser degree and were more dissatisfied with the treatments compared with Swedish patients.

Material and Methods

Participants

The study participants were two groups of patients who received emergency dental treatment, at a public dental-care clinic and the attending dental staff.

The study group consisted of 85 newly arrived adult asylum-seeking refugees from Syria. Asylum seekers are by definition individuals who are not resident in Sweden but who have applied for a residence permit and have stated the reason for fleeing in their application [16]. Adult Swedish patients formed the comparison group with 88 individuals. Finally, the dental staff group included dentists (n = 10), dental hygienists (n = 10) and dental nurses (n = 16) who worked in teams in different constellations during the patient treatments.

The patients were asked consecutively to participate in the study and the common inclusion criterion for both patient groups was adult patients aged > 25 years, as the dental- care system in the County of Västra Götaland involves free dental care up to the age of 24 years for both Swedish citizens and asylum-seeking refugees. Further inclusion criteria for the Syrian patients were: i) asylum-seeking individuals with a valid LMA card (law on the reception of asylum seekers) [17], ii) resident in Sweden for up to two years and iii) Arabic speaking and literate. The additional inclusion criteria for the Swedish control group were: i) Swedish citizen with a Swedish social security number and ii) Swedish speaking and literate. For the dental staff, the inclusion criteria were attendance during the main part of the emergency dental treatment, including the odontological history uptake for the current patients.

Measures

Two questionnaires, one for the patients and one for the dental staff, were produced and designed for this study. Each questionnaire comprised 14 questions with closed answers, where nine questions were the same for both patients and therapists. The questionnaires explored the areas of background data (gender and age), previous information about Swedish dental care, reason for emergency treatment, information, understanding, treatment and the overall impression of the visit. The patients answered the questionnaires individually, but the dental staff answered the questionnaires at theme level, where the therapists gave an overall assessment in each staff-constellation group for each patient.

For the Syrian patients, translations of the written questionnaire and the information consent were made in Arabic. In the translation process [18], the questionnaire and the information were translated into Arabic by a bilingual dentist and then translated back into Swedish by two other bilingual people to verify its compatibility with the original version. For the Swedish patients and the dental staff, the questionnaires were written and answered in Swedish. Prior to the present investigation, a qualitative pilot study of the questionnaires and study information was conducted, after which small adjustments were made.

Data collection

The data collection took place in March-August 2015. In meeting the inclusion criteria and after informed consent, both patients and therapists responded to the questionnaires after the treatments, the patients in a secluded place in the waiting room and the therapists in the treatment room. The completed questionnaires were then left in a locked box. The questionnaires were coded to be able to connect the patient and therapist answers and to distinguish between different patient and therapist group answers in the analyses.

Data processing

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS version 23.0 statistical program. Descriptive statistics, the chi-square test with Pearson’s correlation and the t-test were used in the statistical analysis to describe background data such as gender and age and to compare different group responses to the questionnaires.

The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p ≤ 0.05.

A power calculation was not possible to implement before the study start, as the questionnaires were newly constructed and untested and due to absence of prior experiences in the research field.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Local Human Ethics Committee in Gothenburg (Dnr: 854–14). The authors of the study established an ethical approach according to the World Medical Association, 2017 [19]. The patients and therapists were informed both verbally and in writing about the purpose and organization of the study and that the study was voluntary, which meant that the participants could withdraw their participation at any time, without giving any reason or explanation. Consent to the study was requested and given. All the collected data were treated confidentially and the patients’ identities were not known to anyone other than the treatment staff. The collected data are stored at the R&D Center for primary health care and will be kept there for 10 years.

Results

A total of 88 Syrian patients and 92 Swedish patients were asked for participation in the study. The small dropout of three Syrian and four Swedish patients occurred in connection with the participation request and was mainly due to personal reasons for not wanting to answer the questionnaire. Thus, the study included 85 Syrian and 88 Swedish patients. There were significantly more women in the Syrian patient group (73% vs. 41%, x2 = 22.22, p < 0.001) and the Syrian patients were significantly younger than the Swedish patients (mean age 39.8 yr, SD 14.42 vs. 51.8 yr, SD 14.04, t = –5.27, p < 0.001).

Differences were shown between the two groups of patients in the way they had received information about Swedish dental care before the visit, but also if they had received any information at all (Table 1). Most of the Syrian patients, 95%, reported that they had received information in some way, mainly through verbal information from friends and acquaintances, while 15% of the Swedish patients reported no information at all.

Table 1. The Syrian and Swedish patients’ reported ways of receiving information about Swedish dental care.

|

Ways of receiving information |

Syr pat |

Swe pat |

x2 |

P-value |

|

Through the media |

7 |

28 |

21.32 |

0.000 |

|

From an organization |

25 |

34 |

6.39 |

0.040 |

|

By verbal communication from family or friends |

63 |

23 |

21.57 |

0.000 |

|

Not received any information |

5 |

15 |

7.91 |

0.005 |

Pearson’s chi-square test (p ≤ 0.05), ns = not significant

Syr pat = Syrian patients, Swe pat = Swedish patients

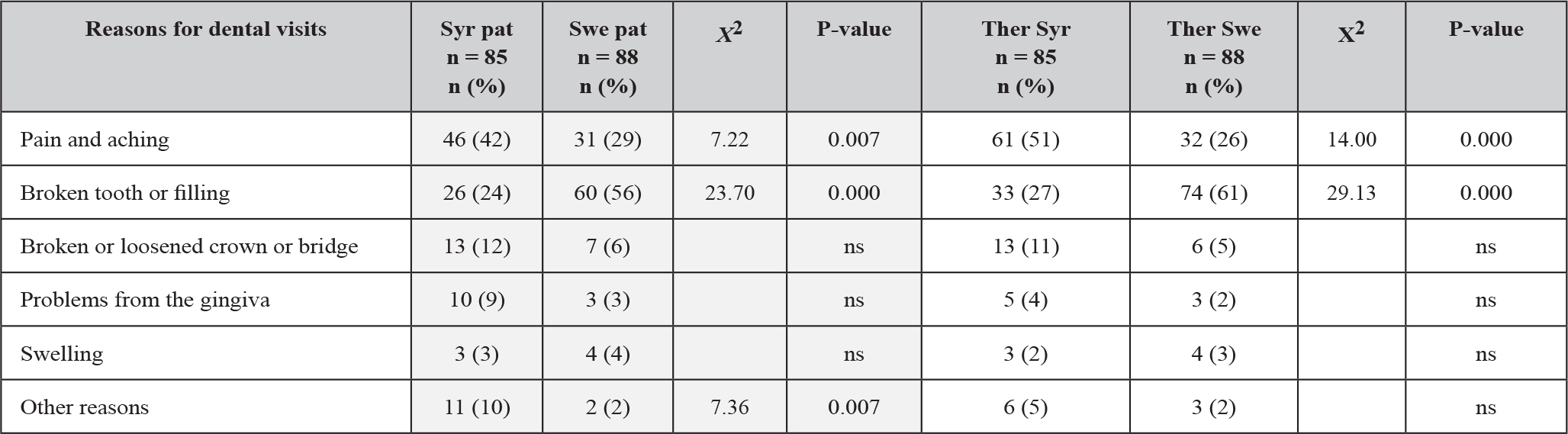

The main reason for the emergency dental visit (Table 2) among Syrian patients was reported to be “pain and aching”, while the Swedish patients reported “a broken tooth or filling”. The therapists’ understanding of the patients’ reasons for the emergency dental visit showed high consistency with the patients’ reports and there were no significant differences between the patients’ and therapists’ answers at group levels or in the matched pair answers (Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Table 2. The Swedish and Syrian patients’ reported reasons for their emergency dental visit and the therapists’ reported perceptions of the patients’ reasons for the visit.

The questionnaire contained multiple-choice answers. Pearson’s chi-square test (p ≤ 0.05), ns = not significant

Syr pat = Syrian patients, Swe pat = Swedish patients, Ther Syr = therapists for Syrian patients, Ther Swe = therapists for Swedish patients.

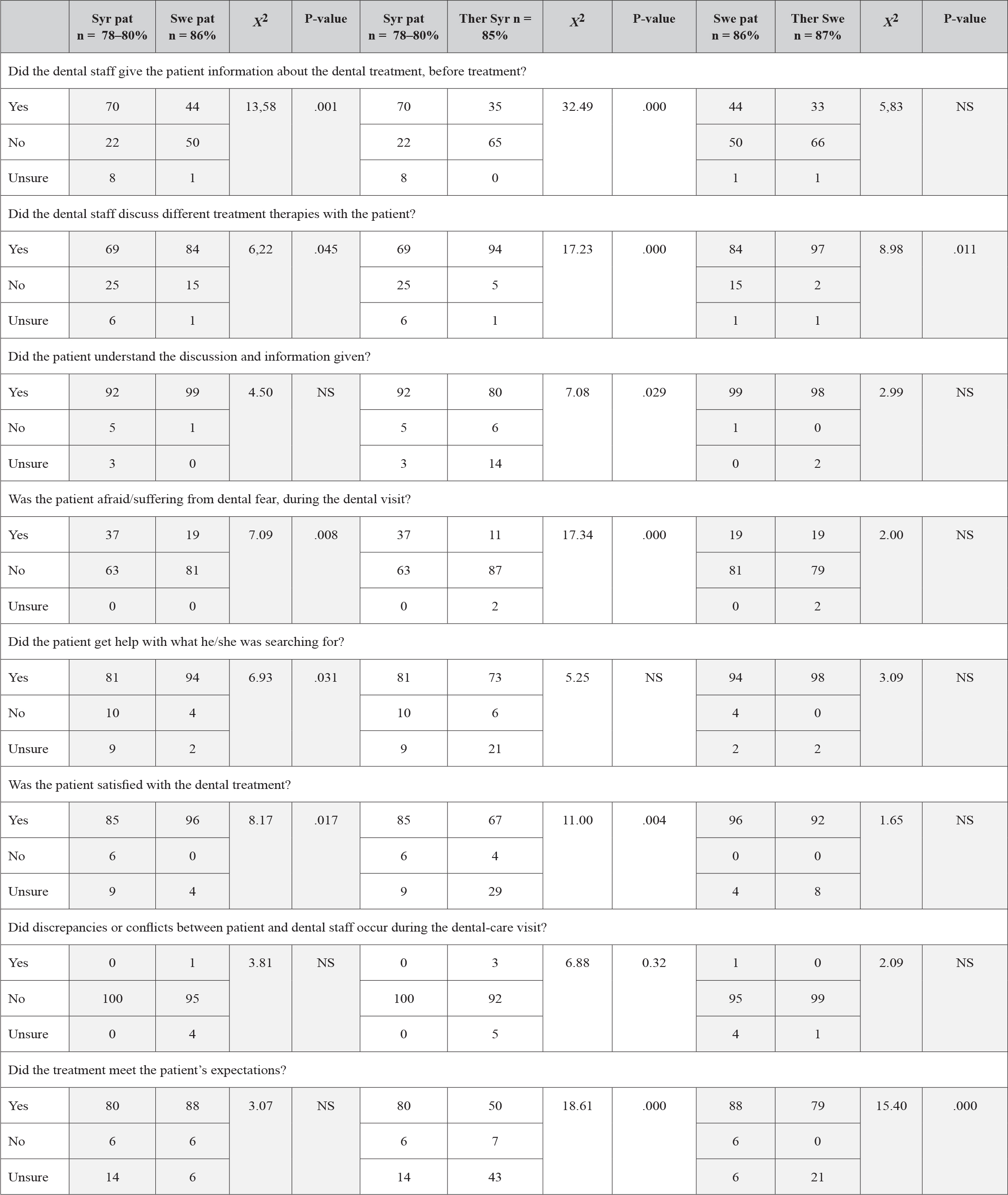

When comparing the Syrian and Swedish patients’ experiences during treatment (Table 3), the Syrian patients reported that they received as much information (70%) as therapy discussion (69%) in connection with the visit, while Swedish patients received therapy discussion to a greater extent (84%) but obtained information to a lesser extent (44%). More than 90% of all the patients in both groups reported that they understood the information and therapy discussion during treatment. About one third of the Syrian patients used an interpreter and a close friend accompanied another third. The Syrian patients experienced more fear during treatment (37%) than the Swedish patients (19%). They also reported less help with what they were searching for and a lower level of satisfaction. Over 80% in both patient groups reported that their expectations of the emergency dental treatment were fulfilled.

Table 3. Comparison between Syrian and Swedish patients and the patients’ and treatment staff’s reported experiences during emergency dental visits.

Pearson’s chi-square test (p ≤ 0.05), ns = not significant

Syr pat = Syrian patients, Swe pat = Swedish patients, Ther Syr = therapists for Syrian patients, Ther Swe = therapists for Swedish patients

The main differences in the patients’/therapists’ reported experiences (Table 3) were the therapists’ greater uncertainty about Syrian patients when it came to the understanding of information and therapy discussion and whether the patients received help or were satisfied with the treatment. However, the therapists expressed no uncertainty, but they did not perceive the Syrian patients fear to the same extent as they did in the Swedish patients. In the overall perception of the emergency dental treatment, the therapists did not realize the degree of fulfilled expectations among Syrian patients, as 43% of the therapists reported that they were unsure. Only at the last question, if the patients’ expectations were met, the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test indicated significant differences in the paired patient-therapist-answers. Both Syrian and Swedish patients were more satisfied with the treatment, than their therapists experienced (Syrian patients Z = 2.81, p<0.005, Swedish patients Z = 2.11, p<0.035).

Discussion

Contrary to what the hypothesis predicted, most Syrian patients reported receiving information about the Swedish dental-care system before treatment, but the information was mostly verbally given by friends and acquaintances. The quality of this information was not investigated in this study.

When information is spread verbally from person to person, there is a risk that it will change and become incorrect and outdated. In order to be able to trust the information, it is important that it is transferred correctly and consistently in accordance with laws and regulations and under controlled conditions [20]. By providing newly arrived individuals with correct information, patients are given the opportunity to access the information before treatment. This makes it possible to create a better understanding and more relevant expectations, as well as to reduce the stress before treatment [20,21].

This could in turn result in fewer feelings of disappointment, sadness and frustration in connection with the therapy discussion and treatment situation when the patient may also suffer acute discomfort, often including pain. For therapists, this can lead to less stressful therapy discussions and treatments and create more stable working situations which, in turn, promotes a better relationship and cooperation with patients and reduces the risk of conflict experiences [22,23].

The hypothesis that Syrian patients were less satisfied with the emergency dental treatments compared with Swedish patients was proven. However, unlike what the therapists experienced, the results also showed that patients’ expectations were mostly met. This reflects one of the main findings of the study, i.e. that the dental staff reported more difficulties interpreting the Syrian patients’ experiences.

One possible reason for the staff’s difficulties interpreting the Syrian patients may be language barriers and/or different ways of expressing thoughts and feelings in terms of both verbal and non-verbal communication. Other possible reasons could be cultural differences in terms of dealing with pain and stress [23,24] or in front of officials, where the level of hierarchy is different. In Sweden, the hierarchical structure is not as powerful as in many other countries, especially in Asian countries, where people tend to accept and act without questioning [25,26]. Swedish patients have more knowledge of their rights and are more used to and comfortable about having to discuss treatment with a therapist. The Swedish Co- determination Act says that therapists are responsible for informing the patient and enabling him/her to participate in the treatment and the decision-making. According to the law, care must be patient focused, equal, safe and conducted in consultation with and with respect for the patient’s self-determination and integrity [25,27]. For many newly arrived individuals, these rights and opportunities for self-influence are a new way of thinking and acting to which they need to relate. Within many cultures, there are also hierarchical differences between the sexes that may involve both culture and religion, where men may have problems respecting and being subordinate to women, such as female dentists, or that women only wish to be treated by other women [7,26,27].

Other constraints, which tend to create gaps in perception, could be the limited time frame for the treatment. In many cases, the therapist works under stress and does not have time to dedicate him/herself fully to the patients [ 28–30]. The staff may also experience difficulties giving information about the limitations in the Swedish dental-care system regarding the treatment of adult asylum seekers, which includes therapy restrictions. This perhaps reflects not only a uncertainty about the interpretation of the patients but also discomfort about making the patients disappointed and anxiety about creating a conflict.

Interestingly, the therapists’ difficulties interpreting Syrian patients also appeared when they did not perceive the fear of these patients during treatment to the same extent as they did with the Swedish patients. This could be due to different ways of expressing fear in different cultures [15,29,30]. It could also reflect the fact that the therapists often lack experiences of being on the run and understanding the stress and fears encountered during the flight. This result indicates that there is a need for further investigations.

Non-tangible assets within Swedish dentistry are the many individuals of foreign descent who work there. The skills and expertise among the staff are not always utilized, but they could be an asset if they convey knowledge and information about their own country of origin and its culture and provide help in interpreting patients. All patients, especially new arrivals, are entitled to an interpreter. Access to an interpreter can be crucial in order to fulfill the right to equal treatment, patient safety and quality of care. Patients’ rights to an interpreter in dental care are not directly stated in the Swedish Dental Care Law or the Patient Act [28,31]. On the other hand, the legislation supports the use of interpreters [9,28].

There may be several possible reasons why the majority of all the patients reported a good understanding of information and the therapy discussion and why the therapists reported a good understanding of the patients’ reasons for seeking emergency care. As an aid to the translation between the Arabic and Swedish languages, interpreters, accompanying close friends or bilingual dentists were used. It should be noted that many adult Syrians are able to master the English language.

The limitations of the study relates to the relatively small sample with only Syrian patients in the study group and not all refugee patients at the clinic and the fact that the study took place at only one dental clinic. The two new survey instruments designed for this study had not been tested before in terms of their validity and reliability. It was therefore not possible to perform a power calculation prior to the start. The authors were aware that an untested questionnaire and a small study sample could result in difficulty obtaining the correct information and to generalize the results. We therefore regard this study as a preliminary exploratory enquiry.

The strength of the study was the small number of missing participants and that, according to our knowledge, no similar study has been conducted previously. From a patient and therapist perspective, the outcome of the study could contribute to a better understanding of the importance of information and different experiences, which points to the need for greater knowledge and training for dental staff in terms of interpretation and communication with individuals from other cultures but also of the impact different cultures have on health care. This could lead to a better understanding, better treatment and increased professionalism, which could in turn affect the efficacy of treatments and rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Syrian refugees as patients are often more satisfied with the emergency dental treatment than the therapists realize and most likely, this conclusion could also apply to refugees from countries other than Syria. Needs have been identified when it comes to the importance of providing correct, consistent information about the Swedish dental-care system to asylum- seeking refugees at an early stage after arriving in Sweden. By extension, needs have also been identified when it comes to the importance of educating dental staff in cultural meetings and communication, as well as increasing their knowledge of different conditions in other countries and cultures.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to all the patients and dental staff who participated in the study. Special thanks go to the clinic manager Sigrid Nilsson, who enthusiastically made it possible to conduct this study at the dental clinic. The study was supported economically and scientifically by R&D Primary Health Care in Västra Götaland.

References

- WHO (2017) Refugee and migrant health. World Health Organization Geneva, USA.

- UNHCR (2017) Figures at a Glance – Statistical Yearbooks. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the UN Refugee Agency.

- https://www.migrationsverket.se/download/18.7c00d8e6143101d166d1aab/1485556214938/Inkomna%20ansökningar%20om%20asyl%202015%20-%20Applications%20for%20asylum%20received%202015.pdf

- Kreps GL, Sparks L (2008) Meeting the health literacy needs of immigrant populations. Patient Educ Couns 71: 328–332.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare (2015) Psykisk ohälsa hos asylsökande och nyanlända migranter. [Mental illness of asylum seekers and newly arrived migrants]. 2015. In Swedish. Available from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/kunskapsstod/2015-1-19.pdf.

- Keboa MT, Hiles N, Macdonald ME (2016) The oral health of refugees and asylum seekers: a scoping review. Globalization and Health 12: 59.

- Smith A, MacEntee MI, Beattie BL (2013) The influence of culture on the oral health- related beliefs and behaviours of elderly chinese immigrants: a meta- synthesis of the literature. J Cross Cult Gerontol 28: 27–47.

- Van Berlaer G, Bohle Carbonell FB, Manantsoa S (2016) A refugee camp in the centre of Europe: clinical characteristics of asylum seekers arriving in Brussels. BMJ Open 6: e013963.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Hälso- och sjukvård och tandvård till asylsökande och nyanlända. [Healthcare and dental care for asylum seekers andnew arrivals]. 2016. In Swedish. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2016-10-13.pdf.

- Ay M, González PA, Delgado RC (2016) The perceived barriers of access to health care among a group of non- camp Syrian refugees in Jordan. Int J Health Serv 0: 1- 24.

- The Swedish Migration Agency. Health care for asylum seekers. 2017. Available from: https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/Private-individuals/Protection-and-asylum-in-Sweden/While-you-are-waiting-for-a-decision/Health-care.html

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Vilken vård ska ett landsting erbjuda asylsökande och papperslösa. [What care should a country council offer asylum seekers and paperless]. 2017. In Swedish. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/stod-i-arbetet/asylsokande-och-andra-flyktingar/halsovard-och-sjukvard-och-tandvard/erbjuden-vard/

- Beiruti N, van Palenstein, Helderman WH (2004) Oral health in Syria. Int Dent J 54: 383–388.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Situation Syrian Regional Refugee Response. 2017. Available from http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/ regional.php

- World Health Organization. Refugee and migrant health; Definitions. 2017. Available from http://www.who.int/migrants/about/definitions/en/ .

- The Swedish Migration Agency. LMA card for asylum seekers. 2017. Available from https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/Private-individuals/Protection-and-asylum-in-Sweden/While-you-are-waiting-for-a-decision/LMA-card.html.

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D (1993) Cross-cultural adaptation of health- related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 46: 1417–1432.

- Swedish guvernement. Lag (2003:460) om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor. [Act (2003:460) concerning the Ethical review of research involving humans]. 2003. Available from

- https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk- forfattningssamling/lag-2003460-om-etikprovning-av-forskning-som_sfs-2003- 460.

- Wångdahl J. Uppfattningar om arbetet med hälsoundersökningar för asylsökande. [Perceptions about the work with health examinations for asylum seekers]. In Swedish. Uppsala University; 2014. Sweden. Available from http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:744594/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Rrustemi I (2003) Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med 57: 503–512.

- Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA (2000) Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med 51: 1611–1625.

- Sofaer S, Firminger K (2005) Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health 26: 513–559.

- Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L (2006) Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 64: 21–34.

- Kotthoff H, Spencer-Oatey H (2007) Chapter 3: Cognitive pragmatic perspective on communication and culture. In: Žegarac VA (ed.), Handbook of Intercultural Communication. Berlin Germany: Mouton de Gruyter Pg No: 31–53.

- Wångdahl J, Lytsy P, Mårtensson L (2015) Health literacy and refugees’ experiences of the health examination for asylum seekers – a Swedish cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 15: 1162.

- The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Föreskrifter och allmänna råd om hälsoundersökningar av asylsökande m.fl. (SOSFS 2011:11). [Regulations and general advices on health assessment of asylum seekers and others]. 2011. In Swedish. Available from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/foreskrifter-och-allmanna-rad/2013-9-5.pdf.

- Karlberg GL, Ringsberg KC (2006) Experiences of oral health care among immigrants from Iran and Iraq living in Sweden. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 1: 120–127.

- Iliadi P (2008) Refugee women in Greece: a qualitative study of their attitudes and experience in antenatal care. Health Sci J 2: 173–180.

- Langan- Fox J, Cooper CL (2011) Chapter 7: Occupational stress among dentists. In: Moore R (ed.), (Part I), Handbook of stress in the occupations. Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar publishing. Pg No: 109–134.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Tolkar för hälso- och sjukvården och tandvården. [Interpreters for healthanddentalcare]. 2016. In Swedish.Available from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2016-5-7.pdf.