Abstract

Objective: To implement an evidence-based sepsis implementation tool for nurses to use when initiating treatment for patients diagnosed with sepsis and to track time of administration of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) 1-hour bundle interventions, mortality, and length of stay.

Design: An evidence-based practice quality improvement (EBP-QI) project.

Setting: A 38-bed observation/short stay unit within a 700-bed hospital in New York City.

Intervention: A sepsis implementation tool was created based on SSC 2018 1-hour guidelines. Sepsis champions delivered education on sepsis recognition, treatment, and management to the nurses, physicians, and other staff.

Main outcome measure: Following the practice change, audits of the sepsis implementation tool were done weekly for 5 months. A target of 85% completion for each of the bundle interventions was set.

Results: From May 8, 2019 to October 8, 2019 a total of 38 patients were diagnosed with sepsis in the emergency department or observation/short stay unit and of these 90% (n=33) had blood cultures drawn twice, 85% (n=34) had stat lactate, and 73% (n=26) had broad-spectrum antibiotics started within 1-hour. The target of 85% was met for 2 of the 3 bundle interventions.

Conclusion: The sepsis 1-hour bundle is best practice however, completion of the bundle interventions within 1-hour of sepsis diagnosis is challenging. In this EBP-QI project, the healthcare staff was successful in completing the majority of the bundle interventions within the hour. Future improvement efforts will focus on improving the initiation of antibiotics within 1-hour of sepsis diagnosis.

Introduction

In the US, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock are associated with 6%, 15%, and 34% mortality rates and respective costs of $16,000, $25,000, and $38,000 per hospitalization [1]. Sepsis is a deadly and costly hospital condition that can be mitigated with early identification and initiation of lifesaving treatment. In 2004 there was a global initiative to bring together critical care and infectious disease experts in the diagnosis and management of sepsis to create the initial Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guidelines to improve awareness and outcomes of sepsis [2]. Initial guidelines included goal directed patient resuscitation during the first 6 hours after recognition, appropriate diagnostic studies to identify cause before initiating antibiotics, and early administration of antibiotics, all to be done as soon as possible within the first 24 hours. Subsequent recommendations in the following years grouped similar interventions into 6 and 3-hour bundles with the expectation that the interventions would all be completed within these shorter time frames. In 2018, the SSC developed the 1-hour sepsis bundle because the 3-hour window was associated with a significant increase in in-hospital mortality [3]. The bundle calls for lactate measures, blood cultures, antibiotics, if appropriate fluid resuscitation and vasopressors within 1-hour of sepsis recognition [3]. In 2015, The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid implemented its core bundle measure for Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle linking reimbursement to a hospitals’ ability to complete the SSC bundle interventions within 3 hours of sepsis recognition [4]. To help meet this quality measure, hospitals may benefit from initiatives aimed at improving the process of sepsis care and bundle completion within the 1 to 3-hour window. Meeting the SSC’s 1-hour implementation goal can be challenging. Historically, nurses have been responsible for initiating a sepsis protocol [5]. There are tools to facilitate timely initiation of bundle interventions [6]. The emergency room nurse sepsis screening tool significantly improved the time to bundle completion in patient’s diagnoses with severe sepsis and septic shock [7]. The nurse initiated emergency department sepsis protocol significantly reduced time to lactate measurements and antibiotic administration [8]. These tools are based on the five steps outlined in the SSC’s 2018 1-hour bundle.

Objective

The purpose of this project was to implement an evidence-based sepsis implementation tool for nurses to use when initiating treatment for patients diagnosed with sepsis and to track time of administration of the bundle elements, mortality, and length of stay.

Methods

Project Design

This EBP-QI project was completed over a 10-month period using a prospective before and after design. This consisted of a 5-month baseline period and a 5-month QI period. In the baseline period, the evidence-based sepsis implementation tool was created, and the sepsis champions delivered education on sepsis recognition, treatment, and management to the nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and other staff, and assessed sepsis knowledge. In the QI period, audits of the sepsis implementation tool were done weekly.

Setting

The Observation/Short Stay Unit (O/SSU) was the project setting. This unit is part of an 800-bed acute-care tertiary hospital in New York City that serves 37,000 patients annually. The hospital has several medical specialties (e.g. cardiology including care of vascular conditions, neurology, and oncology). The O/SSU, is considered part of the emergency department and can take up to 38 patients. O/SSU employs 71 nurses, with an average of 12-14 nurses and 2 charge nurses per shift. There are 2-3 patient care technicians per shift and 1 patient unit assistant for the day and evening shifts. The average daily census ranges from 15 to 35 patients and varies by the time of day. There is a unit nurse manager, assistant nurse manager, and a nurse manager administrative support supervisor. There is a pharmacist on the unit from 0800 to 2400. Between 0001 and 0759, pharmacists are accessible via telephone, and medications are sent via a pneumatic system. Common O/SSU diagnoses include; falls, acute coronary syndrome, transient ischemic attack, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, congestive heart failure, and skin, lung, and urinary infections. The average quarterly sepsis rate was 528 cases for the years 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018, and 84% of these cases were patients with sepsis present on admission.

Participants

Participants were patients entering the hospitals’ emergency department from May 8, 2019 to October 8, 2019 and transferred to the O/SSU and met the following SSC sepsis screening criteria. Patients with 2 or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria or suspected infection defined as sepsis [9] or with septic shock/sepsis-3 defined as organ dysfunction with SIRS criteria (SSC).

Intervention

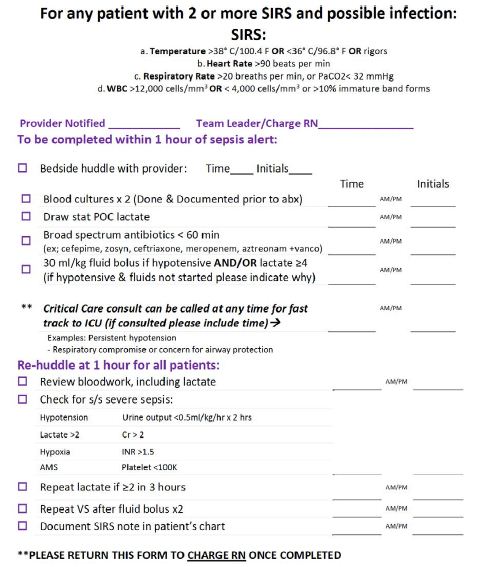

The evidence-based sepsis implementation tool, displayed in Figure 1, was created using SSC’s 2018 guidelines and other evidence source. The nurse immediately notifies the provider when a patient has a positive screen and initiates the sepsis implementation tool with the provider in a safety huddle at the patient’s bedside. The nurse and provider collaborate to provide the first 4 interventions within 1-hour. The nurse documents the time each intervention was completed and initials. Providers document their reasoning for not initiating fluids. The next section of the tool is for nurses to document if a critical care consult was initiated during the first hour. At the 1-hour mark, the nurse and provider re-huddle and perform the next 5 interventions (e.g. review the lab results) to determine if the patient sepsis is worsening. The provider is then required to write a sepsis note in the electronic health record that includes the patient’s presenting condition, completed interventions and subsequent plan of care.

Figure 1: Evidence-Based Sepsis Implementation Tool.

Quality Improvement Process

We used the Revised Iowa Model of Evidence Based Practice to guide this EBP-QI project. The Iowa model uses EBP and QI processes to promote excellence in healthcare [10,11]. This project was led by three individuals with complementary areas of expertise. The project manager was a doctoral-level nursing student with expertise in sepsis recognition, treatment, and management. The physician partner has extensive leadership knowledge and has led numerous multidisciplinary quality and safety initiatives in hospitals. The academic partner has an EBP certification, clinical expertise in critical care nursing, and expertise in dissemination.

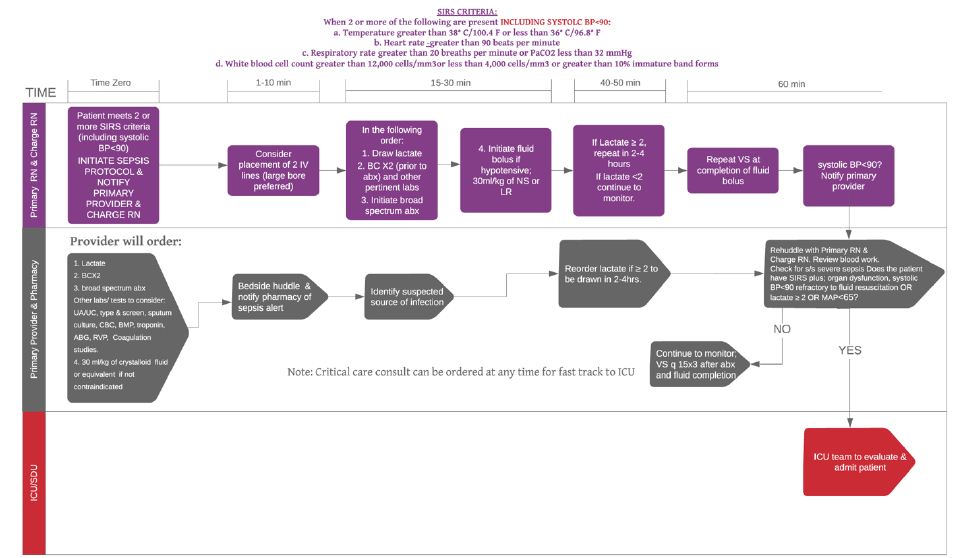

Key stakeholders were the staff nurses and healthcare providers in the O/SSU. To gain their buy in and to form a group of sepsis champions, nurses were reminded that they could submit this project for promotion through a nursing professional advancement program. This strategy resulted in four staff nurses agreeing to be sepsis champions. Physicians and physician assistants interested in sepsis management were also included in the group of champions to help guide and lead other healthcare providers. Initially pharmacists were informed of the QI project to help expedite interventions. They were added as key stakeholders during the 5-month QI period when nurses reported delays in obtaining antibiotics. Our educational strategy was multidimensional and completed over several months. During the first 2 months, we assessed baseline knowledge of sepsis recognition, treatment and management, and attitude toward sepsis care using a questionnaire (See Supplement) that was given to O/SSU nurses and healthcare providers (n=101). We held several meetings to review and discuss questionnaire answers. For the next 3 months, the project manager and sepsis champions gave updates and education as needed at monthly staff meetings, provider meetings, and in real-time in the O/SSU using an iPad. The iPad contained the sepsis checklist, a power-point presentation on sepsis from [9], the sepsis questionnaire answers, and the EBP-QI project goals and intervention description. The iPad was and was left in a central place in the O/SSU that staff could access at any time throughout the 10-month project period. The education for nurses and healthcare providers included review of sepsis recognition and diagnosis, the 1-hour bundle interventions, and the nurse’s role in management including the new sepsis implementation tool. Nurses received additional education on how to complete the sepsis implementation tool and an explanation of the buddy badge strategy to facilitate timely completion of the 1-hour bundle interventions. A badge buddy is a laminated card that attaches to an existing hospital identification badge and lists the SIRS criteria and 1-hour bundle interventions that was given to all O/SSU nurses (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Process Map: Sepsis Algorithm 1-hour Bundle for O/SSU.

The project manager and sepsis champions held monthly group meetings throughout the 10-month project to review the project progress and address any barriers. Champions followed-up with the nurses of patients with delayed bundle interventions within a week to debrief. Monthly emails were sent to all staff with updates on audits and current status of the project including staff feedback regarding barriers to the 1-hour bundle and how to overcome them.

Evaluation Measures

Baseline knowledge of sepsis recognition, treatment and management, and attitude toward sepsis care was measured using an established questionnaire (See Supplement). Adherence was measured by how often the nurses completed the initial lactate measure, blood cultures, and antibiotic administration within the 1-hour window of the patient being diagnosed with sepsis. We set a target of 85% of cases having all interventions completed within 1-hour. Length of stay was measured as the total number of days spent in hospital and mortality was measured as death occurring in the hospital.

Data Collection and Analysis

The completed sepsis implementation tools were retrieved weekly from the O/SSU. The project manager reviewed the tools and checked the electronic health record for 1-hour bundle intervention completion times. Data on mortality and length of stay were obtained after completing chart reviews for the patients included during the QI period (n=38). These data were inputted into an Excel spreadsheet and descriptive statistics were calculated for each outcome [12].

Ethical Considerations

Differentiating Quality Improvement and Research Activities Tool was used to determine that this was a QI project. The project aim was to improve sepsis care for all patients using evidence-based recommendation and no personal health information was collected therefore it did not qualify as human subjects’ research and institutional review board was not needed. Per hospital policy, the project was reviewed and approved by the institution’s Chief Nursing Officer [13].

Actions Taken to Barriers during Baseline QI Period

Table 1 displays the barriers identified by nursing, physicians, and physician assistants during the baseline QI period. These barriers fell into the categories of staffing, factors causing delays and patient specific concerns. Actions taken include; the requirement of two nurses to initiate sepsis protocol interventions, pharmacy added as key stakeholder, nurse to notify pharmacy of patient with sepsis to expedite interventions, notification of 2nd lactate included in the EHR, IV team able to place midlines, central lines, IO kit accessible on the unit, and additional vital sign machines provided. Providers are more vigilant with screening patients prior to arrival. Questionable admissions are evaluated while in the ED by O/SSU providers.

Table 1: Staff Identified Barriers and Actions Taken During Baseline Period.

| Nurses | Attending Physician | Physician Assistant | Pharmacy | Actions Taken |

| Staffing | ||||

| Lack of staff to assist with other patients | Sometimes lack of adequate nursing staff | 2 Nurses are required to carry out sepsis protocol interventions | ||

| Factors causing delays | ||||

| Pharmacy delays | Pharmacy delays | Pharmacy delays | Delay in delivery of antibiotic | Pharmacy added as key stakeholder, nurse to notify pharmacy of patient with sepsis |

| Multiple high acuity patients on the unit at once affecting timing of orders placed | 2nd lactate check delays | Notification of 2nd lactate requirement will be included in the EHR | ||

| Delay in patient recognition | Handoff from emergency department to O/SSU inaccuracy | Time to place central line /IV access | IV team can place lines. New IO kit added to the unit. | |

| Lack of equipment (Vital sign machine, IV access) | Additional equipment is on the unit | |||

| A new electronic method of sepsis protocol initiation and documentation was introduced during the QI period throughout the hospital | Survey sent to all staff to evaluate knowledge of electronic sepsis alert system and education on its use will be provided. | |||

| Patient specific concerns | ||||

| Patients are septic prior to arrival to O/SSU | Providers are more vigilant with screening patients prior to arrival. Questionable patients are evaluated in the ED. | |||

| Trying to manage patients that require aggressive fluid resuscitation and patients that can be conservatively managed with judicious fluid resuscitation | ||||

| Concern for heart failure worsening with IV fluids | ||||

Results

A total of 38 patients entered the hospital’s emergency department from May 8, 2019 to October 8, 2019, transferred to the O/SSU, and had a diagnosis of sepsis. Table 1 displays the completion rates for required bundle interventions in patients diagnosed with sepsis. Blood cultures were completed within an hour on all patients. Initial lactate measures were completed within 1-hour in more than 85% of cases. In 19 of the 26 patients, broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered within 1-hour. The median hospital length of stay was 5 days and no patients died. Staff knowledge scores include a mean score of 57% (0.216) for nurses 60% (0.213) for PA’s and 61% (0.222) for MDs (Table 2).

Table 2: Completion Rates of 1-hour Sepsis Bundle Interventions after Initiating the Sepsis Implementation Tool.

| May 8, 2019 to October 8, 2019 | |

| Bundle Interventions | n=38 |

| f(%) | |

| Blood cultures x 2 (n=38) | 33(100)* |

| Initial lactate (n=34) | 29(85.29)+ |

| Broad spectrum antibiotics (n=26) | 19(73.08)a |

| Hospital length of stay (median, range) | 5 days (1 to 76 days) |

| Mortality | 0 |

*5 had blood cultures drawn before sepsis diagnosis

+4had lactate done before sepsis diagnosis

a12 had antibiotics before sepsis diagnosis

Discussion

We successfully implemented the SSC 1-hour sepsis bundle in our O/SSU. Use of the evidence-based sepsis implementation tool for nurses resulted in exceeding the 85% benchmark for initial lactate measure and blood cultures within 1-hour of the patient being diagnosed with sepsis. However, antibiotic administration within the 1-hour window was achieved 73% of the time. Several experts have proclaimed that the goal for 1-hour antibiotic administration can be unrealistic in certain circumstances and may result in unnecessary antibiotic administration for patients who are not truly septic. Talan suspect that poorer outcome rates will not increase immediately without 1-hour antibiotic therapy for many patients with sepsis. The recommendation is to focus on gaining more insight by improving diagnostic accuracy including antibiotic decision making [14]. The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) withheld its support for the SSC in 2018. One of the reasons includes when and how to use antibiotic prophylaxis and duration of therapy [15]. Additionally, in a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis authors demonstrated no significant survival benefit of administering antibiotics within 3 hours of ED triage or within 1 hour of septic shock recognition in severe sepsis and septic shock [16]. Moreover, the 1-hour bundle poses challenges to providers to send virtually every SIRS positive patient through a rapid sepsis screening which may not be feasible in certain hospital settings including the ED [17].

The median length of stay was 5 days for this quality improvement project. Studies report a decrease or no change in LOS with protocolized care. Threatt [7] reported no change in LOS after implementing the use of a Sepsis Identification Tool using SSC’s guidelines. In contrast, the median length of stay was significantly shorter in the post implementation group in a descriptive retrospective review using qSOFA [18]. Another retrospective observational study reported a decrease in the median LOS after an introduction of a new triage model for sepsis patients from 9 to 7 days [19]. The implementation of an electronic sepsis alert system in the EHR also resulted in a decrease of mean LOS for patients with sepsis from 10.1 to 8.6 days following alert introduction in a time-series study of ED patients with severe sepsis and septic shock [20]. In terms of mortality rate, there were no deaths among the patients diagnosed with sepsis during the QI period. There is conflicting data regarding the relationship between sepsis bundle adherence and mortality rates. The evidence regarding mortality rates demonstrate either no change, or a decrease in the rate. Bruce et al reported no in-hospital mortality rate differences between pre-and post-protocol implementation. Park et al performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of early goal directed therapy (EGDT) using SSC guidelines for treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock and also found no significant difference in mortality between EGDT and control groups. Another study done at a tertiary hospital in Brazil found an overall 44% lower mortality rate and shorter ICU stays for individuals who received a 3-hour bundle compared with others who did not. Moreover, Milano et al performed an observational study and found that among 4,582 patients with sepsis, the overall mortality was lower among those who received bundle-adherent care compared to those who did not.

There were several barriers we encountered during the QI period including pharmacy delays in delivery of antibiotics, delay in patient recognition, 2nd lactate check delays, and lack of adequate nursing staff (Table 1). Several previous studies report similar barriers. A study [21] found that doctors and nurses demonstrated difficulty in identifying septic patients. Results of a cross sectional descriptive study using a self-completed questionnaire given to doctors and nurses related to sepsis identification, principles, resources, skill and education demonstrated that there was a lack of adequate nursing staff, and resources to deliver interventions within the hour [22-30].

Limitations

We focused on patients who arrived through the emergency department and we sent to the O/SSU so the impact of sepsis implementation tool on clinical outcomes in other units (e.g. emergency department, intensive care) is unknown.

A new electronic method of sepsis protocol initiation and documentation was introduced during the QI period throughout the hospital. This may have contributed to an inaccuracy in the documentation of the number of actual patients presenting with sepsis on the O/SSU due to the lack of checklist or electronic use in the EHR.

It is also difficult to determine if having pharmacy as key stakeholders earlier in the project would have affected time to antibiotics. The length of the QI period may also contribute to cyclical differences affecting results. Baseline data does not adequately represent the number of patients that presented with sepsis on the O/SSU. It is difficult to determine which components of the 1-hour bundle will affect patient outcomes. Based on the results, further investigation is needed to determine if the 1-hour bundle affects mortality and LOS.

Conclusion

Utilization of the sepsis 1-hour bundle has demonstrated an increase in timely sepsis management during the QI period. An electronic form of the checklist was added to the EHR system during a new QI cycle, eliminating the need for a paper tool. Completion of the bundle interventions within 1-hour of patients presenting with sepsis is challenging. In this practice change project, the healthcare staff was successful in completing many of the bundle interventions within the hour. Future improvement efforts such as inclusion of pharmacy alert as part of the EHR tool will focus on improving the initiation of antibiotics within 1-hour of sepsis diagnosis

Funding

The authors have no funding source to proclaim.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to proclaim.

References

- Carly J Paoli, Mark A Reynolds, Meenal Sinha, Matthew Gitlin, Elliott Crouser, et al. (2018) Epidemiology and costs of sepsis in the United States — an analysis based on timing of diagnosis and severity level. Crit Care Med 46: 1889-1897. [crossref]

- David L T (2019) Improving Sepsis Bundle Implementation Times: A Nursing Process Improvement Approach. Journal of Nursing Care Quality.

- Levy MM, Evans LE, Rhodes A (2018) The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle: 2018 Update. Critical Care Medicine 46: 997-1000.

- Milano PK, Desai SA, Eiting EA, Hofmann EF, Lam CN, et al. (2018) Sepsis Bundle Adherence Is Associated with Improved Survival in Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health 19: 774-781. [crossref]

- Alberto L, Marshall AP, Walker R, Aitken LM (2017) Screening for sepsis in general hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection 96: 305-315. [crossref]

- Kleinpell R (2017) Promoting early identification of sepsis in hospitalized patients with nurse-led protocols. Critical Care 21. [crossref]

- Threatt DL (2020) Improving Sepsis Bundle Implementation Times: A Nursing Process Improvement Approach. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 35: 135-139. [crossref]

- Bruce HR, Maiden J, Fedullo PF, Son Chae Kim (2015) Impact of Nurse-Initiated Ed Sepsis Protocol on Compliance with Sepsis Bundles, Time to Initial Antibiotic Administration, and In-Hospital Mortality. JEN: Journal of Emergency Nursing 41: 130-137. [crossref]

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC). Hour 1 bundle (2018) Retrieved from http://www.survivingsepsis.org/Bundles/Pages/default.aspx

- Buckwalter KC, Cullen L, Hanrahan K, Kleiber C, McCarthy, et al. (2017) Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice: Revisions and Validation. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 14: 175-182. [crossref]

- Milano PK, Desai SA, Eiting EA, Hofmann EF, Lam CN, et al. (2018) Sepsis Bundle Adherence Is Associated with Improved Survival in Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health 19: 774-781. [crossref]

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, et al. (2017) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Medicine, 3: 304-377. [crossref]

- Foster J (2013) Differentiating quality improvement and research activities. Clinical Nurse Specialist: The Journal for Advanced Nursing Practice 27: 10-13. [crossref]

- Talan DA, Yealy DM (2019) Challenging the One-Hour Bundle Goal for Sepsis Antibiotics. Annals of Emergency Medicine 73: 359-362. [crossref]

- Winslow DL (2018) Why IDSA did not support the surviving sepsis campaign. Infectious Disease Alert 37 Retrieved from https://sacredheart.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.sacredheart.idm.oclc.org/docview/2062753176?accountid=28645

- Sterling SA, Miller WR, Pryor J (2015) The impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes in severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 43: 1907-1915. [crossref]

- Kalantari A, Rezaie S (2019) Challenging the One-Hour Sepsis Bundle. West J Emerg Med 20: 185-190. [crossref]

- Raines K, Sevilla Berrios RA, Guttendorf J (2019) Sepsis Education Initiative Targeting qSOFA Screening for Non-ICU Patients to Improve Sepsis Recognition and Time to Treatment. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 34: 318-324. [crossref]

- Rosenqvist M, Fagerstrand E, Lanbeck P, Melander O, Åkesson P (2017) Sepsis Alert – a triage model that reduces time to antibiotics and length of hospital stay. Infectious Diseases 49: 507-513. [crossref]

- Austrian JS, Jamin CT, Doty GR, Blecker S (2018) Impact of an emergency department electronic sepsis surveillance system on patient mortality and length of stay. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 25: 523-529. [crossref]

- Bentley J, Henderson S, Thakore S, Donald M, Wang W (2016) Seeking sepsis in the emergency department—identifying barriers to delivery of the Sepsis 6. BMJ Qual Improv Rep

- Breen SJ, Rees S (2018) Barriers to implementing the Sepsis Six guidelines in an acute hospital setting. British Journal of Nursing 27: 473-478. [crossref]

- Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients with traumatic brain injury: long-term follow-up of a subgroup of patients from the NICE-SUGAR study (2015) Intensive Care Medicine 6: 1037-1047. [crossref]

- Michael DH, Andrew M D (2017) Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. JAMA 8.

- Mitchell ML, Phillip RD, Sean RT, Walter TLZ, John CM, et al. (2010) The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med 36: 222-231. [crossref]

- Moore LJ, Jones SL, Kreiner LA, et al. (2009) Validating of a screening tool for the early identification of sepsis. Journal of trauma, injury, infection and critical care 66: 1539-1547. [crossref]

- Nagdev AD, Merchant RC, Tirado-Gonzalez A, Sisson CA, Murphy MC (2010) Emergency Department Bedside Ultrasonographic Measurement of the Caval Index for Noninvasive Determination of Low Central Venous Pressure. Annals of Emergency Medicine 55: 290-295. [crossref]

- Picard KM, O’Donoghue SC, Young-Kershaw DA, Russell KJ (2006) Development and implementation of a multidisciplinary sepsis protocol. Critical Care Nurse 26: 43-54. [crossref]

- Pruinelli L, Westra BL, Yadav P, Hoff A, Steinbach M, et al. (2018) Delay Within the 3-Hour Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline on Mortality for Patients With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock*. Critical Care Medicine 46: 500-505. [crossref]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, et al. (2016) The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association 8: 801-810. [crossref]