Abstract

Background: Each year 2.2 million women in Europe die from cardiovascular diseases. The risk of cardiovascular diseases increases from the onset of the menopause and may be reduced by a healthy lifestyle. However, insight in sustainable, effective lifestyle interventions targeted at women around the menopause is lacking. The aim of this study is to find sustainable, effective lifestyle interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk for women (starting) from the menopause, and to investigate effective strategies to enhance adherence.

Methods: Literature search for controlled studies on lifestyle-interventions for women around the menopause, that reported positive effects on cardiovascular risks.

Results: Two dietary interventions, eight exercise programs, three combined programs and one health coaching intervention reported a reduction of cardiovascular risk. The type of diets varies, but common features are reduction of fat and calories and application of behavioral change techniques. The exercise programs apply different types of movement, but are in general supervised group programs. All dietary and exercise interventions are characterized by many contacts and professional guidance. Several strategies to improve treatment adherence are applied such as peer support, telephone calls for missed sessions, self-monitoring and incentives. In general, a high effort to keep women in the program seems to results in relatively good adherence.

Conclusion: Interventions that sustainably reduce cardiovascular risk factors for women starting from the menopause are characterized by intensive strategies such as strict diets, exercise programs with many weekly sessions, guidance by professionals and high efforts to increase adherence. It is the question whether these interventions, tested in a research setting, are applicable and attractive for a large population in daily practice. The challenge is to develop less intensive but sustainable effective interventions that require less strategies to guarantee adhere. Such interventions should be tailored to the specific needs and health problems of women from the menopause.

Keywords

Cardiovascular risk, women, dietary interventions, exercise, menopause, healthy lifestyle

Introduction

Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD) cause more than 4 million deaths each year across Europe, 2.2 million women and 1.8 million men [1]. There are obvious gender differences in the natural history of CVD and in risk pattern [2]. Women are older than men when they develop CVD, and present themselves with different complaints. Cardiovascular events are relatively rare in premenopausal women because of the protective activity of sex hormones during the reproductive age [3]. However, the risk of CVD increases rapidly around the menopause [4]. A healthy lifestyle may reduce this risk [5]. In established guidelines, a six-month lifestyle intervention is recommended in order to reduce cardiovascular risks [6, 7].

Worldwide about 37.5 million women are reaching or currently at the menopause [8], and women may be postmenopausal for 30– 40% of their lives [9]. The need for effective strategies or lifestyle interventions to prevent or postpone CVD in women starting from menopause is therefore high. However, effective lifestyle interventions may not be easy to find, since some studies indicate that lifestyle interventions like diet restriction or increasing physical activity have less effect in women than in men [10-12]. It is unclear whether these differences in effect exist because specific female physiological and psychosocial factors affect effectiveness in itself, because women adhere less to interventions, or both. An intervention can only work if participants adhere to it and adherence is easier when an intervention is appealing and fits into one’s life and situation [13]. Women have different psychological and social mediators of physical activity participation than men [14, 15] and female gender role responsibilities such as care for the family and older parents can lead to decreased participation in physical activity [13, 16] or difficulty with following a diet. In addition, most lifestyle programs have been designed for persons at high risk of CVD in general, and some of these interventions may be less appealing to women. This might be even more the case for women during the menopausal transition, since this period is accompanied with several physiological and psychological complaints, such as tiredness and feelings of depression and musculoskeletal pain [17-20]. Therefore, interventions tailored to this specific group by taking these specific complaints and stage of life into account may be more effective and easier to adhere to. As far as the authors are aware of, insight in sustainable, effective lifestyle interventions specifically targeting women around the menopause is lacking. The present study aims to fill this gap by a systematic search of the literature. In addition, the second objective of this study is to identify strategies that are used to increase adherence to these interventions.

The questions of this literature study are:

• What are sustainable, effective lifestyle interventions (or elements of lifestyle interventions) to reduce the risk of CVD for women starting from the menopause?

• What are effective strategies to enhance adherence to lifestyle interventions for this group of women?

Methods

Search strategy

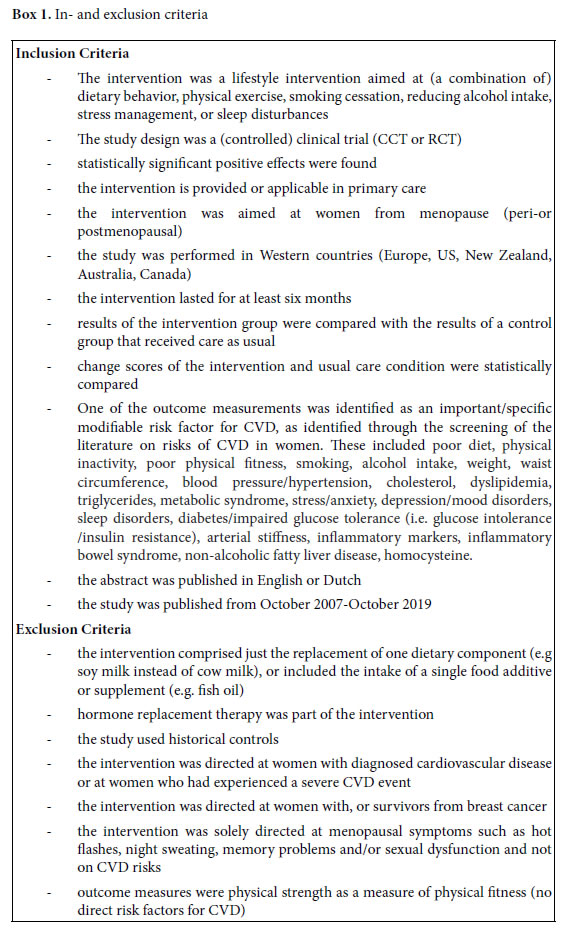

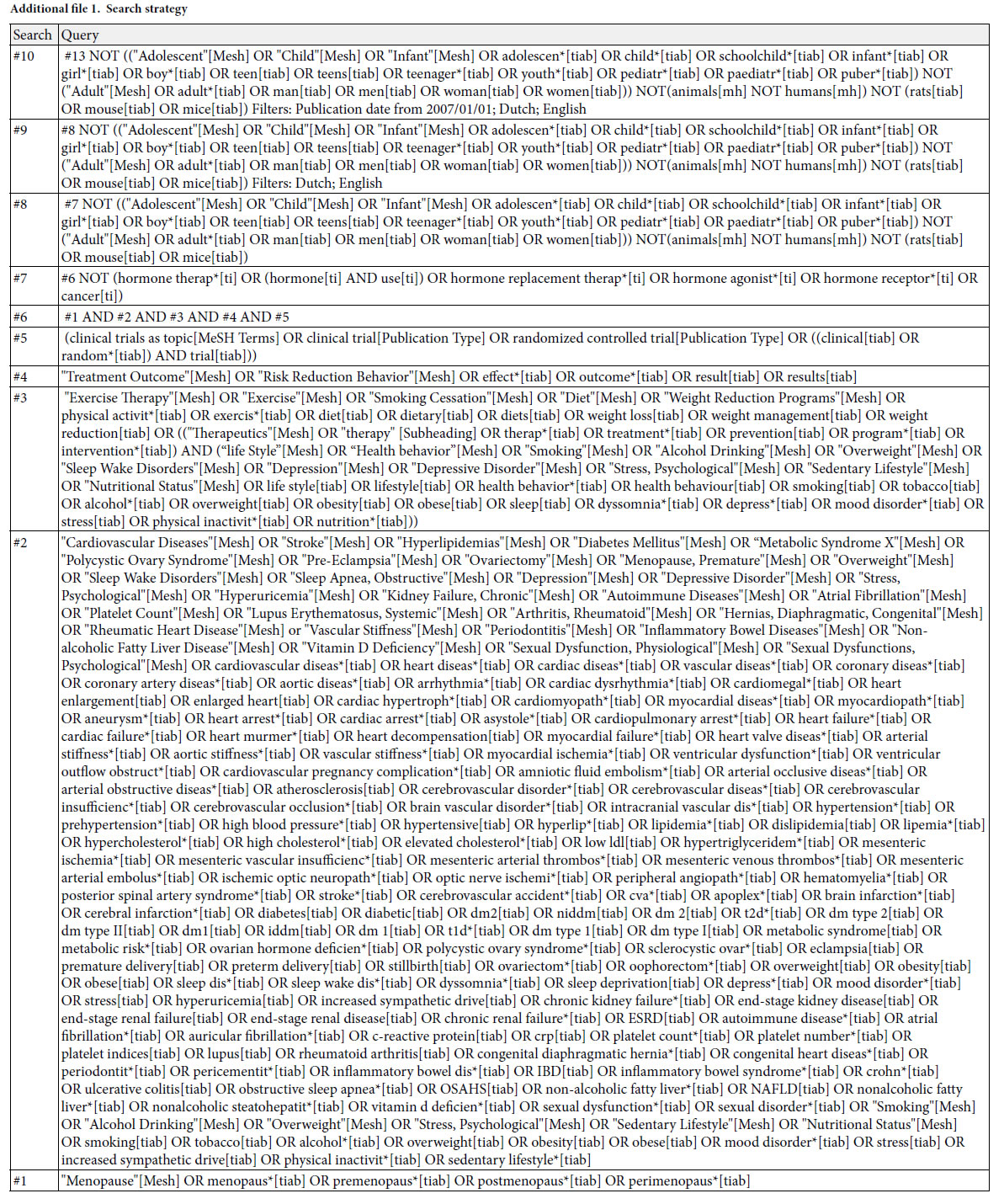

Since our primary aim was to find sustainable, effective lifestyle interventions for women (starting) from the menopause, we only selected studies that reported a significantly positive effect and had a duration of at least six months [6, 7]. Since lifestyle is culturally determined and we searched for interventions that may be applicable in the Dutch primary care or public health domain, only studies from Western countries were included. As preparatory step for our systematic literature search we explored which specific modifiable risk factors and symptoms should be addressed with the intervention, by screening the literature on cardiovascular risks in women [2, 9, 21-35]. Risk factors found were used as search terms in the systematic search for potentially successful interventions. A comprehensive literature search was conducted at October 11th, 2019 in the databases Pubmed, Embase.com, the Cochrane Library, Cinahl (Ebsco), PsycINFO (Ebsco) and Sport Discus (Ebsco). The following concepts were searched (including synonyms and related terms) with controlled terms (MesH in Pubmed, Emtree in Embase, Cinahl Headings, Thesaurus terms in PsycINFO and Sport discus) and free text words: ‘menopause’ AND ‘cardiovascular diseases’ or AND ‘lifestyle interventions’ AND ‘outcome’. The complete search history is presented in the Supplement S1. Reference lists of relevant reviews were screened for additional studies (snowball method). In- and exclusion criteria are presented in Box 1.

Procedure

A random sample of 300 titles and abstracts were scored by one author (CL). The other authors scored each 100 titles and abstracts of this sample (JK, LvD, MV). Since no difference were found between these double scores, the remaining of TIABs were scored by the first author (CL). Scoring of the full text papers and the completion of the tables was performed by CL and checked by JK.

Results

Literature search

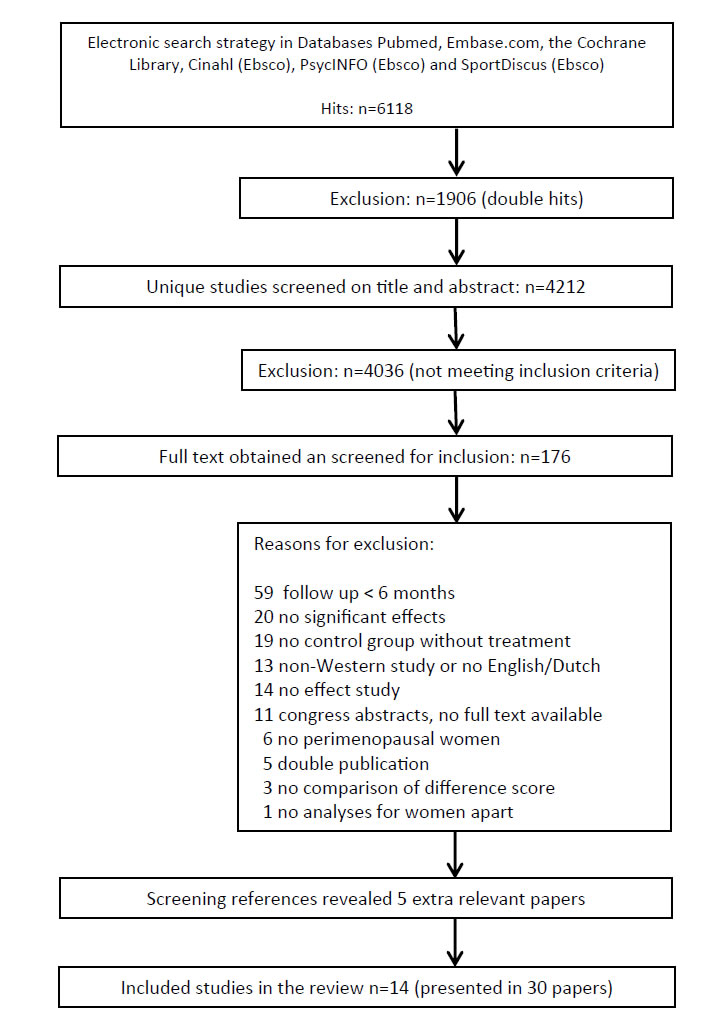

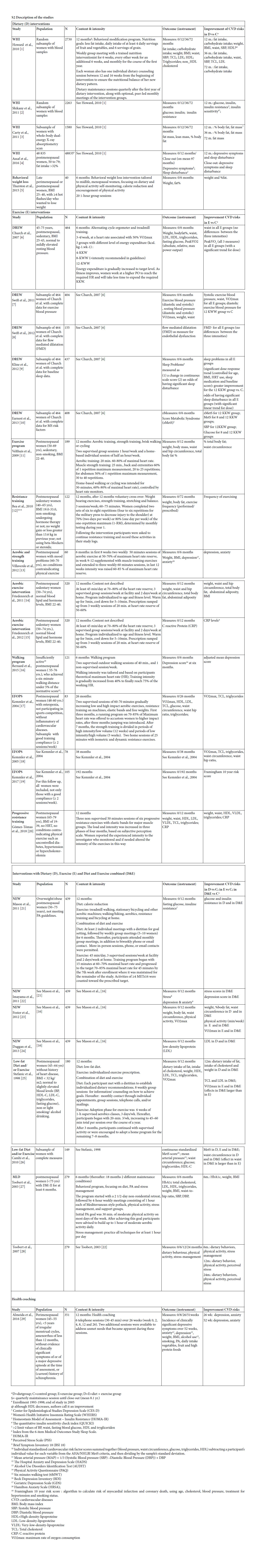

A total of 6,118 hits resulted from the electronic database searches, of which 4,212 were unique. After screening titles and abstracts, 4,036 references were excluded. Of the remaining 176 references, full text was obtained and assessed for inclusion in our study. From this search 25 publications were selected and searching reference lists provided five extra relevant publications. Finally, a total of 30 references, reporting on 13 randomized and trails and one non randomized controlled clinical trial met all inclusion criteria [36-59] (Figure 1). Of these 14 studies, seven were presented in multiple publications. Table 1 in the additional file 2 shows the main characteristics of the 30 included publications.

Study Population

Two studies were found that explicitly focused on women in the menopausal transition [36, 55]. The other studies included postmenopausal women, varying from 40 to 75 years up. For two studies (published in three publications) minimum age is unknown [55-57]. Six studies (14 publications), focused on sedentary women [38, 39, 42-47, 49-51, 54, 58, 59, 61] and four studies (11 publications), specifically on women with overweight [42-45, 49-51, 54, 55, 59]. One study specifically included women with diabetes [56, 57] while six other studies (15 publications) explicitly excluded this group of women [37, 40, 41, 43, 45-49, 51-53, 58, 61, 62]. Most studies excluded women with (a history of) severe health conditions such as cancer, heart disease, dramatically elevated blood levels or mental of psychiatric disorders [36-54, 58, 59, 61-65] or women who had medication for weight loss[43, 45, 49, 51, 55] or for lipids or blood pressure [39, 40,53] or used hormones [46, 47, 55, 58, 62]. Six studies (15 publications) excluded women with excessive alcohol intake [36, 37, 40, 41, 43, 45-49, 51-53, 58, 61]. Almeida et al. specifically included women who suffered from hot flashes [36] and Villaverde Gutiérrez [66] included women with mood problems. In general, studies included a relatively healthy, but overweight and sedentary sample of participants.

Interventions

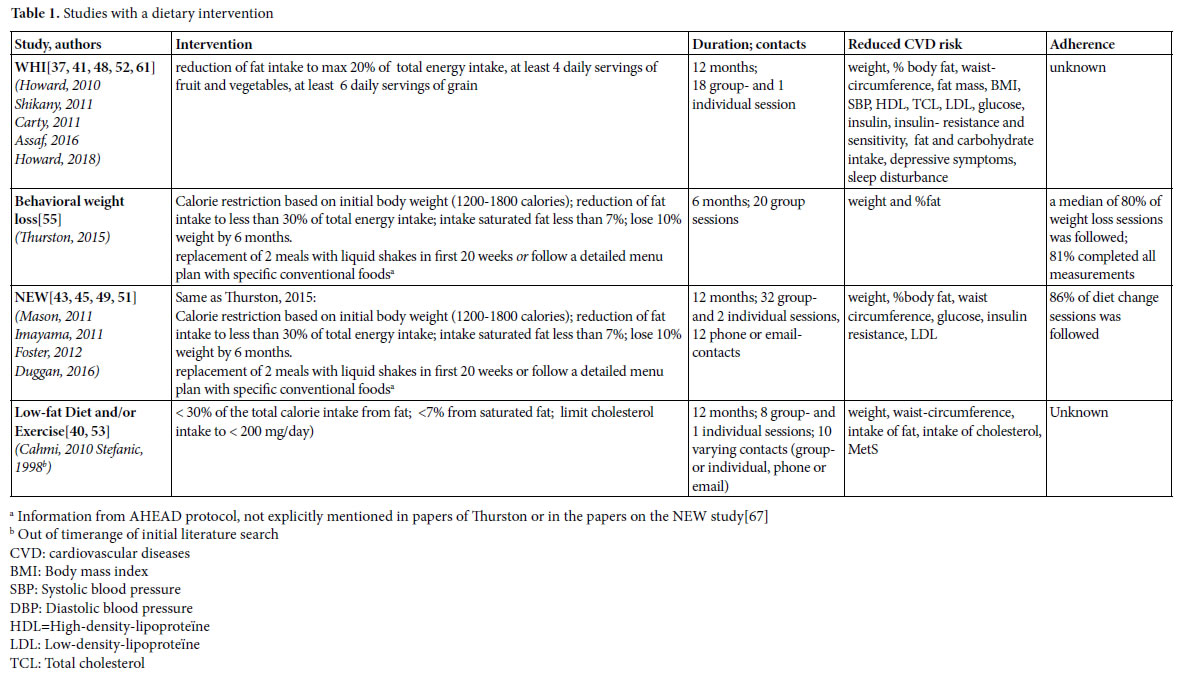

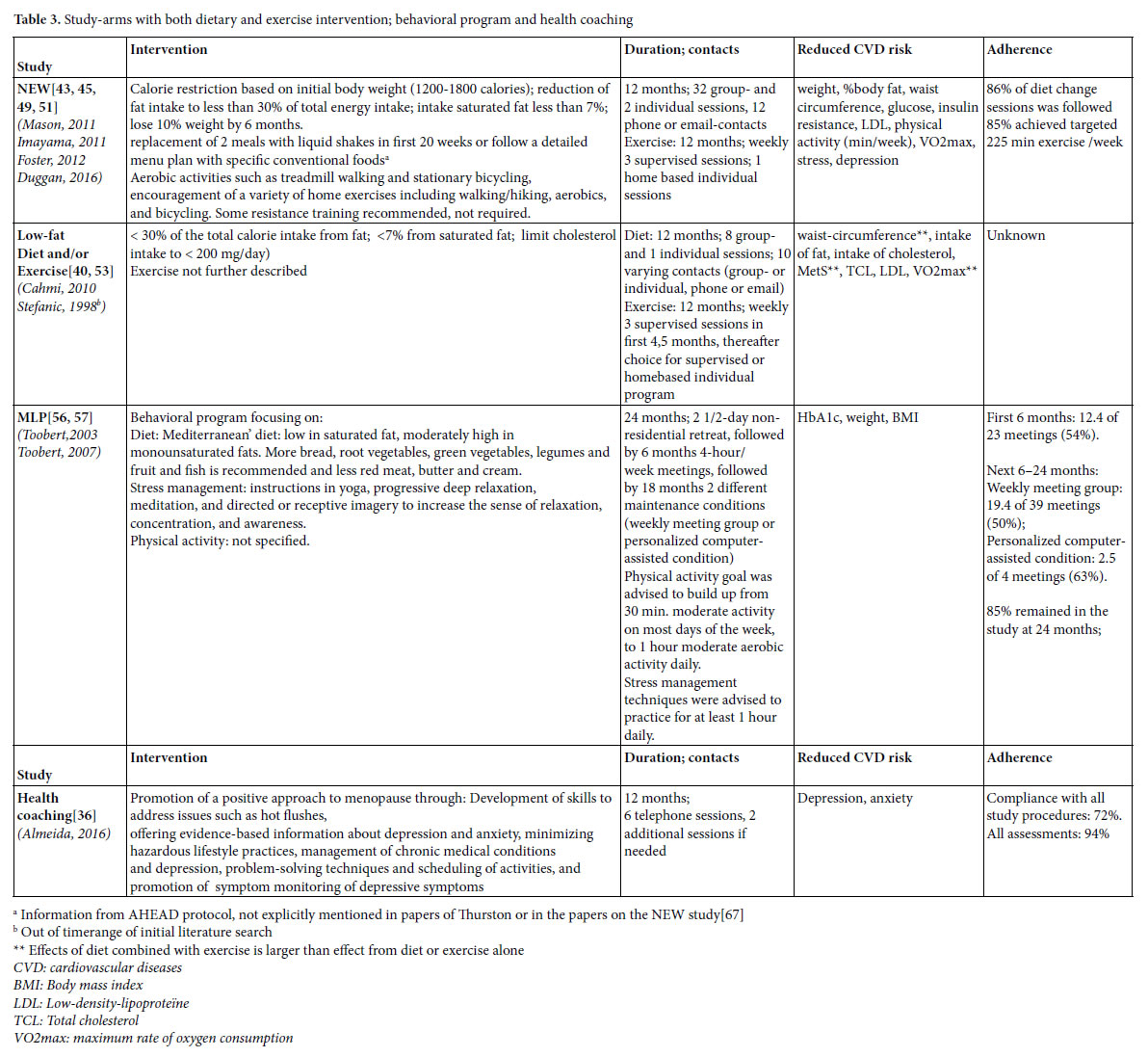

Identified lifestyle interventions can be divided in dietary interventions (Table 1) [37, 40, 41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 51-53, 55, 61] (supervised) physical exercise programs (Table 2) [38-40, 42-47, 49-51, 53, 54, 58, 59, 62-66] a combination of diet and exercise (Table 3), [40, 43, 45, 49, 51, 53, 56, 57] and health coaching (added to Table 3) [36]. Since some studies used a three arms design comparing a dietary intervention with an exercise intervention and with the combination of diet and exercise, these three armed studies are presented in tables 1, 2 and 3. For the readability of this paper, references of the intervention studies are only presented in the tables, and not in the text of the results section.

Dietary interventions

We found four studies with positive effects of a dietary intervention on the reduction of risk factors for CVD (table 1). The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study implements a change of eating behavior rather than a prescribed diet. The behavioral weight loss study of Thurston and the Nutrition and Exercise in Women study (NEW) were based on the Look AHEAD [67] and Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) [68]. In the AHAED protocol, it is recommended to replace 2 meals with liquid shakes in the first 20 weeks or follow a detailed menu plan with specific conventional foods [67] a strategy that is also used in the DPP to individuals who have difficulty achieving the weight loss goal. The Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise intervention of Cahmi et al. and Stefanic et al. was based on the National Cholesterol Education Program Step II Guidelines. All these interventions focused on a reduction of calorie and (saturated) fat intake, and did not solely focus on nutritional requirements, but also addressed different behavioral components, and strategies to increase adherence.

Behavioral components and other strategies to increase adherence with dietary interventions

Because the focus in the WHI study was on changing eating behavior rather than on following a prescribed diet, behavioral components were explicitly addressed. Women were assigned to a group of 12 members in which psychological and behavioral themes such as motivation and reinforcements, social influence and support, time management, problem-solving and coping with stress, and relapse prevention were discussed. Nutrition and behavioral strategies were integrated into each session. The first sessions focused on knowledge of sources of fat and nutrition skills such as shopping and adaptation of recipes, and later sessions emphasized behavioral skills.

In the NEW study and in the behavioral weight loss intervention of Thurston each session started with a weigh-in and women were asked to fill in food dairies which were provided with feedback. Meal replacements were offered for free [67]. The behavioral weight loss intervention of Thurston et al. was a combination of individual sessions en group sessions to enhance social support. Participants were called by professionals or other group members when they missed meetings. The program was tailored to menopausal women by addressing issues such as dietary and activity choices in context of sleep loss; behavior change in the context of family, work, and caretaking demands; and physical activity choices with aging [55]. The participants in the Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise intervention of Cahmi et al. and Stefanic et al., met with a dietitian to establish individualized dietary recommendations and received counseling on how to achieve dietary goals through group sessions. They had monthly contact through individual appointments, group sessions, telephone calls, and/or mailings.

Effects

The dietary interventions reduce cardiovascular risks and effects are found on a variety of outcomes (table 1). Although the sizeof the effects of the studies are difficult to compare because participants and measurement procedures differ, effects seem to be small to moderate in general.

Adherence

In the behavioral weight loss study, participants followed a median of 80% of the weight loss sessions and 81% of the participants completed all measurements. In the NEW study, the participating women followed 86% of the diet change sessions. The WHI study and the Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise study reported no information on adherence.

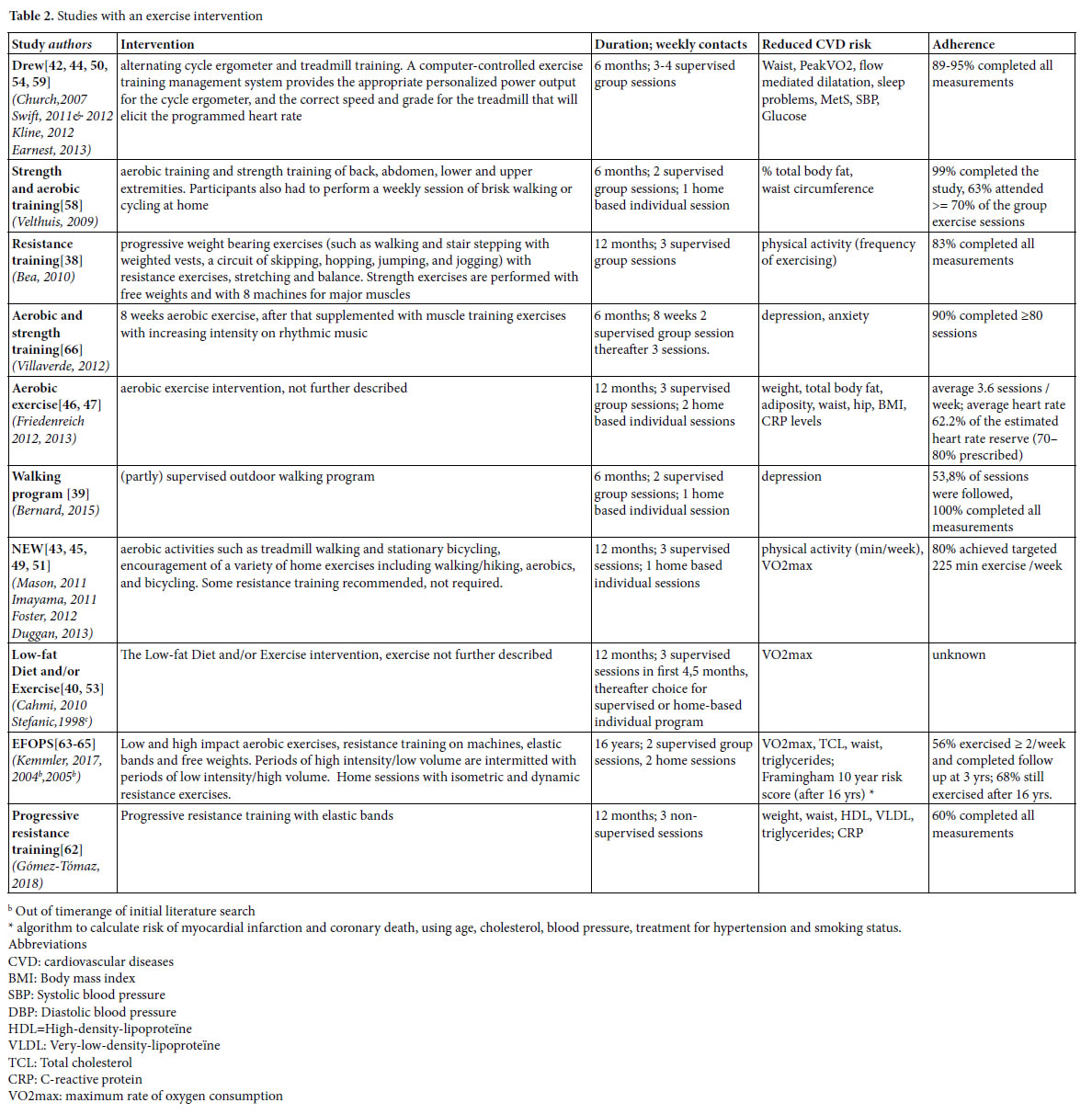

Exercise interventions

We found 10 studies (21 papers), with positive effects of an exercise intervention on the reduction of risk factors for CVD (Table 2). In the Dose Response to Exercise in Women (DREW) study, three intensities of cycle ergometer and treadmill training were compared with a control condition. The effects of strength and aerobic training were studied by Velthuis et al., by Villaverde Gutiérrez et al., in the exercise condition of the NEW study and in the EFOPS study. Friedenreich et al. studied the effects of an aerobic exercise intervention, but gave no details about the content, and also the exercise component of Low- fat Diet and/or Exercise intervention studied by Cahmi et al., and by Stefanic et al., was not described. Bea et al., and Gómez-Tomáz et al., studied the effects of progressive resistance training and Bernard et al., the effects of a walking program.

Strategies to increase adherence with exercise interventions

In the DREW study, participants started with six information sessions that emphasized the relevance of a healthy life and providing recommendations for healthy diet, stop smoking and alcohol reduction. Educational materials were distributed. Women were contacted when they missed a scheduled exercise session and heart rate monitors were distributed to monitor the (max 16) unsupervised exercise sessions that were allowed. Each woman was given up to $500 as an incentive to complete the study. In the aerobic exercise intervention studied by Friedenreich et al., heart rate monitors and weekly exercise logs were used to monitor adherence. Educational packages were provided that addressed relevant issues for women starting with exercising. The exercise program consisted of group sessions to permit interaction between participants. Women were contacted when they missed sessions and awarded when program milestones were reached.

The resistance training studied by Bea et al. encompassed a variety of reinforcement strategies to motivate participants such as education and skill development, self-efficacy, incentive programs, social support, and modeling. Participation was based on individual improvement rather than competition among participants. A social environment was created that challenged the women to improve their daily exercise performance. The support program further included exercise and goal-setting logs, regularly testing to monitor progress, and personal contracts. The strength and aerobic training of Velthuis et al., also used diverse techniques to enhance adherence such as group exercise sessions in combination with an individual program, personal feedback, realistic and regularly updated individual goals, and exercise logs to track frequency and duration of exercise. Training intensity was controlled by heart rate monitors. In the NEW study, session attendance was tracked to promote and monitor adherence. Women not meeting exercise targets were contacted to discuss barriers and approaches to increase activity. Exercise physiologists met regularly with a clinical health psychologist experienced in lifestyle behavior change to discuss participant progress and refine behavior modification goals according to each participant’s needs. Villaverde Gutiérrez et al., mentioned no specific adherence strategies other than social interaction with the group and the research team and a motivating approach from the trainer. In the EFOPS study, individual training logs were used to monitor attendance and compliance. Both The Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise study, and the study of Gómez- Tómas et al., on progressive resistance training, gave no information about adherence enhancing measures.

Effects

Just as the dietary interventions, the exercise interventions reduce cardiovascular risks. Diverse outcomes were measured with diverse instruments. Effects seem to be larger with increasing training intensity.[42, 44, 50].

Adherence

Adherence varied and was expressed in different manners, such as completion of planned measurements and/or attendance of the exercise sessions. In general, completion rates of the studies was high. In the walking program of Bernard et al., all participating women completed the measurements, in the strength and aerobic training programs 90- 99%, in the DREW study 89-95%, and in the study on resistance training 83%. In the EFOPS study, 78%, 79% and 69% of the women completed the measurements at two, three and 16 years follow up.

Attendance of sessions is measured differently. In the NEW study, 80% of the participants achieved the targeted 225 weekly minutes of exercise, in the aerobic exercise study of Friedenreich et al., women followed on average 3.6 of the required five weekly exercise sessions, in the strength and aerobic training 63% of the women attended more than 70% of the required sessions, and in the walking program 54% of the sessions were followed. In the EFOPS study, after three years 56% attended two of more training sessions and after 16 years, 69% of the women still exercised. The Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise study reported no information on adherence.

Interventions with a combination of diet and physical exercise

Three studies were found that combined diet and exercise (Table 3). The earlier described NEW study and Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise intervention used a three armed design and compared the effects

of diet, with those of exercise and with those of the combination of diet and exercise. Toobert et al., [56, 57] studies the effects of the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program (MLP), an intervention focusing on diet, physical exercise and stress-management together.

Behavioral components and other strategies to increase adherence

Components of the NEW study and the Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise are described earlier. The behavioral components of MLP were based on combined Social Cognitive Theory, Goal Systems, and Social Ecological Theory. Participants were able to set personal lifestyle change goals at the start of the intervention, and received ongoing peer and professional support for their goals throughout the treatment program. To enhance adherence, participants kept a log of adherence to the diet (self-monitoring), contests with cash prize were held, incentives such as small presents were given, and participants were called by professionals or group members when meetings were missed.

Effects

The combined interventions reduce cardiovascular risks and effects are found on a variety of outcomes (Table 3). In general, effects are larger than those achieved with a dietary program or physical exercise alone.

Adherence

In the NEW study 86% of diet change sessions was followed and 85% of the women complied with the targeted 225 minutes weekly exercise. In the MLP study, 85% of the women remained in the study after two years, but attendance of the meetings itself was rather poor. In the first 6 months 54% of the meetings were attended. In the next 18 months, 50% of the meetings were attended by the group that received weekly (follow up) meetings, while in the follow up condition with personalized computer-assistance attendance of the sessions was 63%. Adherence in the Low-fat Diet and/or Exercise study was not described.

Health Coaching

Almeida studied the effects of a health coaching program and found an effect on depression and anxiety. The intervention was delivered by a trained psychologist. Ninety-four percent of the women completed all measurements and 72% complied with all study procedures.

Discussion

We found 14 lifestyle interventions that report a sustainable reduction of cardiovascular risk in (post)menopausal women. These interventions apply dietary guidance, exercise programs, health coaching, or a combination of these elements. Although the type of prescribed diet varies, reduction of fat and calories are common features and all dietary interventions apply behavioral change techniques. The exercise programs vary in type of movement, but almost all are group based, supervised by a professional and performed in a fitness center, except the progressive resistance training of Gómez- Tómas et al. which was monitored on a distance by the principal investigator [62] and Bernard et al.’s walking program [39]. Exercises are in general of modest intensity. Most interventions, dietary as well as exercise programs, are characterized by very large number of contacts. Dietary guidance is given in group sessions, supplemented with individual face to face contacts, phone calls and/or emails. The number of exercise sessions varies from three to five times a week, with a mix of supervised exercises and home assignments. Furthermore, in all interventions participants are intensively guided by several highly educated professionals such as dietitians, fitness-trainers, physiotherapists, physiologists, stress-management instructors, and professional or lay support group leaders.

Although it is difficult to estimate the magnitude of the effects in the studies, effects seem to be small to moderate. Apparently, even a relatively small reduction of cardiovascular risks such as blood pressure and weight with lifestyle interventions requires much time and effort. However, especially in postmenopausal women even small weight loss or prevention of further weight gain and deterioration of blood values is clinically relevant [69]. Effects were largest when diet and exercise were combined, a finding that corresponds with international literature on lifestyle interventions in the general population [70] and postmenopausal women [71]. Although the studies provide insufficient information to relate effects to the specific elements of the intervention (type of diet or exercise), a cautious conclusion may be that the exact content of an intervention matters less, as long as the interventions are intensive enough and participants adhere. This is consistent with a meta-analysis of Johnston on the effectiveness of different diet programs, who suggested that patients may best choose the diet that gives them the least challenges with adherence [72, 73]. There is little reason to believe that this is different for exercising.

It is obvious that adherence to lifestyle-interventions is an important issue, and a second aim of our study was to determine which strategies are effective to enhance adherence for women around the menopause. Although not all studies describe adherence strategies in detail, several strategies are found (Tables 1-3). Especially dietary interventions use behavioral strategies to stimulate sustainable lifestyle changes such as provision of knowledge, problem solving and coping strategies, goal setting and training of skills. Both dietary and exercise interventions used peer support to enhance adherence to the sessions, by offering the intervention in a group, and in several studies participants were telephoned when they missed a session. Progress and adherence was measured through self-monitoring and in some studies incentives up to cash prizes of 500 dollar were given. In general, it seems that a high effort to keep women in the program results in relatively good adherence. The EFOPS study seems to be an exception to this, because no real strategies to increase adherence are applied and yet 67% of women still exercise after 16 years. Women were able to choose to participate in the exercise group themselves, and the authors interpret their results as a further indication that lifelong training is reserved for highly motivated postmenopausal women who are willing and able to attend intensive training programs [63].

The high frequency of sessions, intensive guidance of professionals and the high effort to enhance adherence in the studies indeed raise the question whether the found interventions are applicable to a large

population in daily practice. It is recognized that behavioral change such as adapting a healthy lifestyle takes time and effort. However, in the Dutch health care system, dietary guidance is reimbursed for three hours a year, unless patients are additionally insured. Most exercise programs found were performed in supervised fitness centers, and the interventions may be too expensive for some women, especially for women from a lower socioeconomic status who are more at risk for cardiovascular disease. So it is important to find other ways to achieve the same results, for example with the use of blended care in which face to face contacts with a professional in a group are combined with a Health support or through telephonic contacts such as in the health coaching intervention of Almeida [36].

In addition to possible financial barriers, it can be doubted whether such intensive physical exercise programs and diets appeal to women. Especially in the menopausal transition, women often suffer from musculoskeletal pain [17-20] which may increase with intensive exercising. Mood and stress disorders accompanying the menopause and demands from everyday family life or work, may interfere with the strict dietary demands. Remarkably, only two studies were found that focused explicitly on women in the menopausal transition and their specific health problems [36, 55]. The rather strict dietary intervention of Thurston addresses issues as dietary and activity in context of sleep loss, family, work and caretaking demands, and reduces weight and fat% [55]. Thurston also showed that women who lost weight experienced less hot flushes, and participating women reported that this was a motivator to adhere to the study.

The health coaching intervention from Almeida promotes a positive approach of the menopause and diminishes depression and anxiety [36]. The other 9 studies however, also included post- menopausal women, some of them closely around the menopause, but others up to the age of 79 years [37]. So there is obviously a gap in the literature regarding effective lifestyle programs for women in the menopausal transition. Also Jull et al. who performed a review on lifestyle interventions targeting body weight changes during the menopause transition only found one randomized (western) study from 2003 [74].

Still, we argue that the onset of the menopause could just be a good starting point for changing lifestyle, since lifestyle interventions not only reduce cardiovascular risks, but may also diminish specific symptoms of the menopause. Reductions in weight, BMI and abdominal circumference have been associated with a reduction in vasomotor symptoms and physical exercise may reduce feelings of depression and stress [55, 75, 76]. Prerequisites for such lifestyle interventions are that they are attractive for women around the menopause, take their day to day (menopausal) health problems into account and fit into women’s life and daily routines [13, 15]. In our study we have focused on interventions with sustainable, positive effects on cardiovascular risks and the result is that we have found relatively intensive interventions, that may appeal less to this group. The search for, or development of interventions that are less intensive but still effective in reducing cardiovascular risks for women around the menopause is challenging. To reduce cardiovascular risks, people should preferably change their lifestyle for the rest of their life, so strategies need to be realistic. Based on life style coaching approaches used in the Diabetes Prevention Program, Vendetti et al assumed that problem solving approaches and self-monitoring tools are essential to overcome barriers to adhere to a healthy diet and physical activity [15] so these elements should be incorporated in future interventions. Finally, we think that it is very important to take the views and experiences of the target group itself into account in the development of such strategies.

Limitations of the Study

The purpose of this study was to provide an overview of sustainable, effective lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD for women (starting) from the menopause. For that reason we selected studies that reported significant positive effects on cardiovascular risks in our target population. As a result, our study cannot be interpreted as a systematic overview of all types of interventions aiming at reducing cardiovascular risks. However, the effective interventions or elements of these interventions that were found, can be used as a starting point for further development of more feasible interventions, and by professionals in daily practice to guide women who want to decrease their CVD risk. The strength of our study is that we only selected randomized studies, which offers the highest level of evidence. A disadvantage is however, that these studies often include a relatively healthy sample of participants, which limits the generalizability to daily practice.

Conclusion

There are interventions that sustainably reduce cardiovascular risk factors for women from the menopause. These interventions are characterized by intensive strategies such as meal replacements and frequent exercise sessions, frequent personal, face to face contacts, and great efforts to increase adherence. Apparently, lowering cardiovascular risks through lifestyle interventions demands considerable efforts from women, health care providers, trainers and coaches to guarantee effects and adherence. The question is whether large scale implementation is feasible with regard to costs, willingness of the target group and capacity of the professionals. The challenge is to develop sustainable effective interventions that are less intensive and require less strategies to guarantee adhere. These interventions should be tailored to the specific needs and health problems of women from the menopause, and best be developed in dialogue with the target group itself.

Supplements

S1: Search strategy. The document describes the search strategy across electronic databases and search engines.

S2: Characteristics of the included studies.

Competing Interest

Liset van Dijk received funding from Astra Zeneca, Pfizer and Abbvie for studies not related to this study; Marcia Vervloet received funding from Pfizer and Abbvie for studies not related to this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Dutch Heart Foundation.

Authors’Contribution

CL, JK, LvD and MV developed the design of the study and screened abstracts and titles. CL and JK screened full texts and performed the analysis. All co-authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. CL and JK drafted the manuscript and all co-authors commented on the draft and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Linda Schoonmade, information specialist for designing and piloting search terms and performing the electronic searches.

References

- Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, et al., (2016) Cardiovascular disease in Europe: Epidemiological update 2016. European heart journal 37: 3232-3245. [crossref]

- Mosca L, Benjamin, EJ, Berra, K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, et al., (2011) Effectiveness- Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women-2011 Update: A Guideline From the American Heart Association. Circulation 123: 1243- 1262.

- Mercuro G, Deidda M, Bina A, Manconi E, Rosano GM (2011) Gender-specific aspects in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Current pharmaceutical design 17: 1082-1089. [crossref]

- Vassalle C, Simoncini T, Chedraui P, Perez-Lopez FR (2012) Why sex matters: The biological mechanisms of cardiovascular disease. Gynecological endocrinology 28: 746-751. [crossref]

- Wenger NK (2011) What do the 2011 American Heart Association guidelines tell us about prevention of cardiovascular disease in women? Clinical cardiology 34: 520-523. [crossref]

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults JAMA cardiology 2001, 285:2486-2497.

- Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. The Evidence Report. Rockville; 1998.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Menopause: Women’s Reproductive Health http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/WomensRH/Menopause.htm

- Collins P, Rosano G, Casey C, Daly C, Gambacciani M, et al., (2007) Management of cardiovascular risk in the peri-menopausal woman: A consensus statement of European cardiologists and gynaecologists. European heart journal 28: 2028-2040. [crossref]

- Flodgren G, Deane K, Dickinson HO, Kirk S, Alberti H, et al., (2010) Interventions to change the behaviour of health professionals and the organisation of care to promote weight reduction in overweight and obese people. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 3: 000984. [crossref]

- Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SA, et al., (2015) Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis 241: 211-218. [crossref]

- Leblanc V, Begin C, Hudon AM, Royer MM, Corneau L, et al., (2014) Gender differences in the long-term effects of a nutritional intervention program promoting the Mediterranean diet: Changes in dietary intakes, eating behaviors, anthropometric and metabolic variables. Nutrition journal 13: 107. [crossref]

- Segar M, Jayaratne T, Hanlon J, Richardson CR (2002) Fitting fitness into women’s lives: effects of a gender-tailored physical activity intervention.Women’s Reproductive Health http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/WomensRH/Menopause.htm

- Egli T, Bland HW, Melton BF, Czech DR (2011) Influence of age, sex, and race on college students’ exercise motivation of physical activity. Journal of American college health. J Am Coll Health 59: 399-406. [crossref]

- Venditti EM, Wylie-Rosett J, Delahanty LM, Mele L, Hoskin MA, et al., (2014) Short and long-term lifestyle coaching approaches used to address diverse participant barriers to weight loss and physical activity adherence. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 11: 16. [crossref]

- Verhoef MJ, Love EJ, Rose MS (1992) Women’s social roles and their exercise participation. Women & health 19: 15-29. [crossref]

- Depypere H, Pintiaux A, Desreux J, Hendrickx M, Neven P, et al., (2016) Coping with menopausal symptoms: An internet survey of Belgian postmenopausal women. Maturitas 90: 24-30. [crossref]

- Dugan SA, Powell LH, Kravitz HM, Everson Rose SA, et al. (2006) Musculoskeletal pain and menopausal status. The Clinical journal of pain 22: 325-331. [crossref]

- Frange C, Hachul H, Hirotsu C, Tufik S, Andersen ML, et al., (2018) Insomnia with Musculoskeletal Pain in Postmenopause: Associations with Symptoms, Mood, and Quality of Life. Journal of menopausal medicine 24: 17-28. [crossref]

- Hoga L, Rodolpho J, Goncalves B, Quirino B (2015) Women’s experience of menopause: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI database of systematic reviews and implementation reports 13: 250-337. [crossref]

- Campesi I, Franconi F, Seghieri G, Meloni M (2017) Sex-gender-related therapeutic approaches for cardiovascular complications associated with diabetes. Pharmacological research 119: 195-207. [crossref]

- Charkoudian N, Rabbitts JA (2009) Sympathetic neural mechanisms in human cardiovascular health and disease. Mayo Clinic proceedings 84: 822-830. [crossref]

- Collins P, Webb CM, de Villiers TJ, Stevenson JC, Panay N, et al., (2016) Cardiovascular risk assessment in women – an update. Climacteric 19: 329-336. [crossref]

- Di Giosia P, Passacquale G, Petrarca M, Giorgini P, Marra AM, et al., (2017) Gender differences in cardiovascular prophylaxis: Focus on antiplatelet treatment. Pharmacological research 119: 36-47. [crossref]

- Di Pilla M, Bruno RM, Taddei S, Virdis A (2016) Gender differences in the relationships between psychosocial factors and hypertension. Maturitas 2016, 93: 58-64. [crossreff]

- Katsiki N, Mikhailidis DP (2015) Emerging Vascular Risk Factors in Women: Any Differences from Men? Current medicinal chemistry 22: 3565-3579. [crossref]

- Llaneza P, Garcia-Portilla MP, Llaneza-Suarez D, Armott B, Pérez-López FR, et al., (2012) Depressive disorders and the menopause transition. Maturitas 71: 120-130. [crossref]

- McKibben RA, Al Rifai M, Mathews LM, Michos ED (2016) Primary Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Women. Current cardiovascular risk reports 10: 01.

- Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK (2011) Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: What a difference a decade makes. Circulation 124: 2145-2154. [crossref]

- Pedersen LR, Frestad D, Michelsen MM, Mygind ND, Rasmusen H, et al., (2016) Risk Factors for Myocardial Infarction in Women and Men: A Review of the Current Literature. Current pharmaceutical design, 22: 3835-3852. [crossref]

- Prata J, Ramos S, Martins AQ, Rocha-Goncalves F, et al., (2014) Women with coronary artery disease: Do psychosocial factors contribute to a higher cardiovascular risk? Cardiology in review 22: 25-29.

- Roberts ME, Davis, LL (2013) Cardiovascular Disease in Women: A Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Prevention. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2013: 679-687.

- Stranges S, Guallar E (2012) Cardiovascular disease prevention in women: A rapidly evolving scenario. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases 22: 1013-1018. [crossref]

- Vitale C, Mendelsohn ME, Rosano GM (2009) Gender differences in the cardiovascular effect of sex hormones. Nature reviews Cardiology 6: 532-542. [crossref]

- Vitale C, Miceli M, Rosano GM (2007) Gender-specific characteristics of atherosclerosis in menopausal women: risk factors, clinical course and strategies for prevention. Climacteric 2: 16-20. [crossref]

- Almeida OP, Marsh K, Murray K, Hickey M, Sim M, et al., (2016) Reducing depression during the menopausal transition with health coaching: Results from the healthy menopausal transition randomised controlled trial. Maturitas 92: 41-48. [crossref]

- Assaf AR, Beresford SA, Risica PM, Aragaki A, Brunner RL, et al., (2016) Low- Fat Dietary Pattern Intervention and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 116: 259-271. [crossref]

- Bea JW, Cussler EC, Going SB, Blew RM, Metcalfe LL, et al., (2010) Resistance training predicts 6-yr body composition change in postmenopausal women. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 42: 1286-1295. [crossref]

- Bernard P, Ninot G, Bernard PL, Picot MC, et al., (2015) Effects of a six-month walking intervention on depression in inactive post-menopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Aging & mental health 19: 485-492. [crossref]

- Camhi SM, Stefanick ML, Katzmarzyk PT, Young DR (2010) Metabolic syndrome and changes in body fat from a low-fat diet and/or exercise randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 18: 548-554. [crossref]

- Carty CL, Kooperberg C, Neuhouser ML, Tinker L, Howard B , et al., (2011) Low- fat dietary pattern and change in body-composition traits in the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 93: 516-524. [crossref]

- Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN (2007) Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: A randomized controlled trial. Jama 29: 2081-2091. [crossref]

- Duggan C, Tapsoba JD, Wang CY, Campbell KL, Foster-Schubert K , et al., (2016) Dietary Weight Loss, Exercise, and Oxidative Stress in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 9: 835- 843. [crossref]

- Earnest CP, Johannsen NM, Swift DL, Lavie CJ, Blair SN, et al., (2013) Dose effect of cardiorespiratory exercise on metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. The American journal of cardiology 111: 1805-1811. [crossref]

- Foster-Schubert KE, Alfano CM, Duggan CR, Xiao L, Campbell KL, et al., (2012) Effect of diet and exercise, alone or combined, on weight and body composition in overweight-to-obese postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 20: 1628- 1638. [crossref]

- Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Woolcott CG, Wang Q, Stanczyk FZ, et al., (2012) Inflammatory marker changes in a yearlong randomized exercise intervention trial among postmenopausal women. Cancer prevention research 5: 98-108. [crossref]

- Friedenreich CM, Woolcott CG, McTiernan A, Terry T, Brant R, et al., (2011) Adiposity changes after a 1-year aerobic exercise intervention among postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. International journal of obesity 35: 427-435. [crossref]

- Howard BV, Curb JD, Eaton CB, Kooperberg C, Ockene J, et al., (2010) Low-fat dietary pattern and lipoprotein risk factors: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 91: 860-874. [crossref]

- Imayama I, Alfano CM, Kong A, Foster-Schubert KE, Bain CE, et al., (2011) Dietary weight loss and exercise interventions effects on quality of life in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 8: 118. [crossref]

- Kline CE, Sui X, Hall MH, Youngstedt SD, et al., (2012) Dose-response effects of exercise training on the subjective sleep quality of postmenopausal women: exploratory analyses of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open 2.

- Mason C, Foster-Schubert KE, Imayama I, Kong A, Xiao L, et al., (2011) Dietary weight loss and exercise effects on insulin resistance in postmenopausal women. American journal of preventive medicine 41: 366-375. [crossref]

- Shikany JM, Margolis KL, Pettinger M, Jackson RD, Limacher MC, et al., (2011) Effects of a low-fat dietary intervention on glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Dietary Modification trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 94: 75-85. [crossref]

- Stefanick ML, Mackey S, Sheehan M, Ellsworth N, Haskell WL, et al., (1998) Effects of diet and exercise in men and postmenopausal women with low levels of HDL cholesterol and high levels of LDL cholesterol. The New England journal of medicine 339: 12-20. [crossref]

- Swift DL, Earnest CP, Blair SN, Church TS (2011) The effect of different doses of aerobic exercise training on endothelial function in postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: results from the DREW study. Br J Sports Medicine 46: 753- 758. [crossref]

- Thurston RC, Ewing LJ, Low CA, Christie AJ, Levine MD, et al., (2015) Behavioral weight loss for the management of menopausal hot flashes: a pilot study. Menopause 22: 59-65. [crossref]

- Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Barrera M, Radcliffe JL, et al., (2003) Biologic and quality-of-life outcomes from the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes care 26: 2288-2293. [crossref]

- Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Barrera M, Ritzwoller DP, et al., (2007) Long- term effects of the Mediterranean lifestyle program: a randomized clinical trial for postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 4:1. [crossref]

- Velthuis MJ, Schuit AJ, Peeters PH, Monninkhof EM. (2009) Exercise program affects body composition but not weight in postmenopausal women. Menopause 16: 777- 784. [crossref]

- Swift DL, Earnest CP, Katzmarzyk PT, Rankinen T, Blair SN, et al., (2012) The effect of different doses of aerobic exercise training on exercise blood pressure in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. Menopause 19: 503-509. [crossref]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS medicine 6: 1000100. [crossref]

- Howard BV, Aragaki AK, Tinker LF, Allison M, Hingle MD et al., (2018) A Low- Fat Dietary Pattern and Diabetes: A Secondary Analysis From the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. Diabetes care 41: 680-687. [crossref]

- Gomez-Tomas C, Chulvi-Medrano I, Carrasco JJ, Alakhdar Y (2018) Effect of a 1-year elastic band resistance exercise program on cardiovascular risk profile in postmenopausal women. Menopause 25: 1004-1010. [crossref]

- Kemmler W, Kohl M, von Stengel S (2017) Long-term effects of exercise in postmenopausal women: 16-year results of the Erlangen Fitness and Osteoporosis Prevention Study (EFOPS). Menopause 24: 45-51. [crossref]

- Kemmler W, Lauber D, Weineck J, Hensen J, Kalender W, et al., (2004) Benefits of 2 years of intense exercise on bone density, physical fitness, and blood lipids in early postmenopausal osteopenic women: results of the Erlangen Fitness Osteoporosis Prevention Study (EFOPS). Archives of internal medicine 164: 1084-1091. [crossref]

- Kemmler W, von Stengel S, Weineck J, Lauber D, Kalender W, et al., (2005) Exercise effects on menopausal risk factors of early postmenopausal women: 3-yr Erlangen fitness osteoporosis prevention study results. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 37: 194-203. [crossref]

- Villaverde Gutierrez C, Torres Luque G, Abalos Medina GM, Argente del Castillo MJ, Guisado IM, et al., (2012) Influence of exercise on mood in postmenopausal women. Journal of clinical nursing 21: 923-928. [crossref]

- Look AHEAD Research Group, Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, Jakicic J (2006) The Look AHEAD Study: A Description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity 14: 737-752. [crossref]

- (1999) The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care 22: 623-634. [crossref]

- Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR. (2000) Weight gain during menopause. Is it inevitable or can it be prevented? Postgraduate medicine 108: 46-53. [crossref]

- Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P (2014) Diet or exercise interventions vs combined behavioral weight management programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 114: 1557-1568. [crossref]

- Cheng CC, Hsu CY, Liu JF (2018) Effects of dietary and exercise intervention on weight loss and body composition in obese postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause 25: 772-782. [crossref]

- Sharma AM (2015) Weight-loss diets only work when you follow them. Evidence- based medicine 20: 103-104.

- Johnston BC, Kanters S, Bandayrel K, Wu P, Naji F et al. (2014) Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis. Jama 312: 923-933. [crossref]

- Jull J, Stacey D, Beach S, Dumas A, Strychar I, et al., (2014) Lifestyle interventions targeting body weight changes during the menopause transition: a systematic review. Journal of obesity 2014: 824310. [crossref]

- North American Menopause Society (2004) Treatment of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 11: 11-33. [crossref]

- Huang AJ, Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, Hernandez AL, et al., (2010) An intensive behavioral weight loss intervention and hot flushes in women. Archives of internal medicine 170: 1161-1167. [crossref]

Supplementary Information

References

- Howard BV, Curb JD, Eaton CB, Kooperberg C, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and lipoprotein risk factors: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 91(4):860-874.

- Shikany JM, Margolis KL, Pettinger M, Jackson RD, et al. Effects of a low-fat dietary intervention on glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Dietary Modification trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2011, 94(1):75-85.

- Carty CL, Kooperberg C, Neuhouser ML, Tinker L, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and change in body-composition traits in the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2011, 93(3):516-524.

- Assaf AR, Beresford SA, Risica PM, Aragaki A, et al. Low-Fat Dietary Pattern Intervention and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2016, 116(2):259-271.

- Thurston RC, Ewing LJ, Low CA, Christie AJ, et al. Behavioral weight loss for the management of menopausal hot flashes: a pilot study. Menopause (New York, NY) 2015, 22(1):59-65.

- Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 2007, 297(19):2081-2091.

- Swift DL, Earnest, C.P., Blair, S.N., Church, T.S. The effect of different doses of aerobic exercise training on endothelial function in postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: results from the DREW study. Br J Sports Medicine 2011, 46(10):753-758.

- Swift DL, Earnest CP, Katzmarzyk PT, Rankinen T, et al. The effect of different doses of aerobic exercise training on exercise blood pressure in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. Menopause (New York, NY) 2012, 19(5):503-509.

- Kline CE, Sui X, Hall MH, Youngstedt SD, et al. Dose-response effects of exercise training on the subjective sleep quality of postmenopausal women: exploratory analyses of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open 2012, 2(4).

- Earnest CP, Johannsen NM, Swift DL, Lavie CJ, et al. Dose effect of cardiorespiratory exercise on metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. The American journal of cardiology 2013, 111(12):1805-1811.

- Velthuis MJ, Schuit AJ, Peeters PH, Monninkhof EM. Exercise program affects body composition but not weight in postmenopausal women. Menopause (New York, NY) 2009, 16(4):777-784.

- Bea JW, Cussler EC, Going SB, Blew RM, et al. Resistance training predicts 6-yr body composition change in postmenopausal women. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2010, 42(7):1286-1295.

- Villaverde Gutierrez C, Torres Luque G, Abalos Medina GM, Argente del Castillo MJ, et al. Influence of exercise on mood in postmenopausal women. Journal of clinical nursing 2012, 21(7-8):923-928.

- Friedenreich CM, Woolcott CG, McTiernan A, Terry T, et al. Adiposity changes after a 1-year aerobic exercise intervention among postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. International journal of obesity (2005) 2011, 35(3):427-435.

- Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Woolcott CG, Wang Q, et al. Inflammatory marker changes in a yearlong randomized exercise intervention trial among postmenopausal women. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2012, 5(1):98-108.

- Bernard P, Ninot G, Bernard PL, Picot MC, et al. Effects of a six-month walking intervention on depression in inactive post-menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Aging & mental health 2015, 19(6):485-492.

- Kemmler W, Lauber D, Weineck J, Hensen J, et al. Benefits of 2 years of intense exercise on bone density, physical fitness, and blood lipids in early postmenopausal osteopenic women: results of the Erlangen Fitness Osteoporosis Prevention Study (EFOPS). Archives of internal medicine 2004, 164(10):1084-1091.

- Kemmler W, von Stengel S, Weineck J, Lauber D, et al. Exercise effects on menopausal risk factors of early postmenopausal women: 3-yr Erlangen fitness osteoporosis prevention study results. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2005, 37(2):194-203.

- Kemmler W, Kohl M, von Stengel S. Long-term effects of exercise in postmenopausal women: 16-year results of the Erlangen Fitness and Osteoporosis Prevention Study (EFOPS). Menopause (New York, NY) 2017, 24(1):45-51.

- Gomez-Tomas C, Chulvi-Medrano I, Carrasco JJ, Alakhdar Y. Effect of a 1-year elastic band resistance exercise program on cardiovascular risk profile in postmenopausal women. Menopause (New York, NY) 2018, 25(9):1004-1010.

- Mason C, Foster-Schubert KE, Imayama I, Kong A, et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise effects on insulin resistance in postmenopausal women. American journal of preventive medicine 2011, 41(4):366-375.

- Imayama I, Alfano CM, Kong A, Foster-Schubert KE, et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise interventions effects on quality of life in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2011, 8:118.

- Foster-Schubert KE, Alfano CM, Duggan CR, Xiao L, et al. Effect of diet and exercise, alone or combined, on weight and body composition in overweight-to-obese postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2012, 20(8):1628-1638.

- Duggan C, Tapsoba JD, Wang CY, Campbell KL, et al. Dietary Weight Loss, Exercise, and Oxidative Stress in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2016, 9(11):835-843.

- Stefanick ML, Mackey S, Sheehan M, Ellsworth N, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in men and postmenopausal women with low levels of HDL cholesterol and high levels of LDL cholesterol. The New England journal of medicine 1998, 339(1):12-20.

- Camhi SM, Stefanick ML, Katzmarzyk PT, Young DR. Metabolic syndrome and changes in body fat from a low-fat diet and/or exercise randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2010, 18(3):548-554.

- Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Barrera M, et al. Biologic and quality-of-life outcomes from the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes care 2003, 26(8):2288-2293.

- Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Barrera M, et al. Long-term effects of the Mediterranean lifestyle program: a randomized clinical trial for postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2007, 4:1.

- Almeida OP, Marsh K, Murray K, Hickey M, et al. Reducing depression during the menopausal transition with health coaching: Results from the healthy menopausal transition randomised controlled trial. Maturitas 2016, 92:41-48.